The opening image of Billy Wilder’s film noir masterpiece, Sunset Boulevard, captivated audiences when it premiered in 1950: a man’s corpse floating in a swimming pool owned by a faded Hollywood starlet. How did he end up there? Who killed him? The tone was ominous, the danger real, yet due to decades of screen and print copycats, the same scene today has become a crime story cliché—think, for instance, of the needlepoint parody of the facedown murder victim in the poster for the 1996 Coen Brothers’ film, Fargo. Nevertheless, Ross McMeekin confidently opens his pulpy debut novel, The Hummingbirds, with a variation on this classic setup. As the reader is dropped into the water with protagonist Ezra Fog—a noir name if there ever was one—McMeekin keeps his prose lean, offering six brief paragraphs that leave no room for overindulgence or cornball characters. And you know what? It works. Ezra, pistol-whipped and toppled from a boat, treads in “the vast maw” of the Pacific, under a sky full of “smeared” stars, far from the shoreline. Nobody speaks. Everything is relayed as action punctuated with precise details, and as Ezra fights to stay afloat, like Wilder before him, McMeekin whisks the reader into the past, ready to set the tragedy of Ezra Fog into motion from square one.

The Hummingbirds is a literary beach read that isn’t afraid to steer its characters into grim territories, a modern noir that’s easily consumable, but which contains evocative character beats. When we’re reintroduced to Ezra, nine days earlier, he’s the groundskeeper for former Hollywood “It Girl” Sybil Harper and her older producer husband, Grant Hudson. Ezra lives in Harper and Hudson’s pool house and takes photographs of hummingbirds in his spare time. His handsomeness leads many to question his ambitions in the land of beautiful faces, but Ezra shuns the possibility of stardom, and like all good noir heroes, his outsider status and dark past keeps him humble. Early on, Ezra recounts standing on a beach as a child with his mother, the leader of a religious cult, and waiting for an apocalypse that never occurs. Ezra’s mother kills herself via self-immolation a short time later, and the whirlwind of these early years of alienation carves Ezra into the modest, artistic man who Sybil takes a shine to, and who Grant grows to distrust. When Grant is off to Vancouver for work, Sybil, the femme fatale recently off her meds, begins to flirt with Ezra. She skinny-dips while Ezra stares on from his window, and it isn’t long before an affair blossoms.

Ezra is the character meant to most closely represent the reader, the observer who finds himself strung up in a series of webs, but McMeekin eschews the more obvious choice of 1st-person perspective in The Hummingbirds for that of close 3rd-person throughout. This lets the author bounce around his trio’s thoughts, and frequently when doing so, small actions trigger long recollections. The story of Ezra’s mother comes alive in these moments, as does Sybil’s history with Grant, and Grant’s own rough and tumble childhood. Over the course of a few seconds of actual time, McMeekin’s characters journey through Thomas Bernhardian reflections. Ezra, Sybil, and Grant embrace their archetypes in these reveries, yet McMeekin adds emotional depth to elevate them above their expected stations. For example, the morning after initially sleeping with Ezra, Sybil contemplates her own value while showering and brushing her hair. At age 35, she sees her career as over: “Who wanted complexity from her? All these films and photo shoots betrayed a bitchy vixen with simplistic desires. And people, all these people, they assumed that her typecast role was a thinly veiled biography.” Here, McMeekin forces the character to confront her own limitations, adding self-awareness often lacking in standard noir. Sybil doesn’t want to be the femme fatale, yet this is her role. By excavating each character’s psyche, the novel’s nine-day timeline expands, dipping decades into the past to round out the present. It’s a wise choice that creates an intimate story of three people and one setting while never reading as claustrophobic.

Still, while The Hummingbirds is a fun ride, it has flaws, particularly the narrative plateau created as Sybil and Ezra take comfort with each other. Happiness doesn’t work in noir, and these scenes read as padding. Though the lovebirds talk of running away together, seasoned readers know this tire spinning exists solely for a third act explosion. Thankfully, McMeekin’s secret weapon is Grant, a better-looking Snidely Whiplash of a villain, and once he returns from his travels, the novel burns its way to the finish line. Grant is the perfect character to root against, a stand-in for real world creeps, a poster boy for toxic masculinity who blames his past for his present woes and settles scores with intimidation and manipulation. But like so many powerful men today, he’s also a bulletproof boogeyman who seemingly cannot be stopped. Grant has political ambitions, and discovering a cheating wife could be the sympathy card he needs to rebuild himself as a trustworthy candidate. His cleverness has the potential to not only drive a wedge between Ezra and Sybil, but to destroy their lives. And since the reader knows Ezra will wind up swimming for his life eventually, it’s hard to hold out hope as the trio plays a game of cat and mouse in the novel’s closing pages.

To say anything else would ruin the ending of The Hummingbirds, though I will add that at one point, a downtrodden Ezra wanders into a movie theater showing one of Sybil’s recent features, only to discover it’s an NC-17 reflection of his own life: a gardener romanced by his sexy employer. Shrewd moments like this keep the reader turning the page, confident that McMeekin is aware of the tropes he’s juggling. In The Hummingbirds, noir tales of yore are saluted as McMeekin adds his own flavor to the mix, and the result is a nimble excursion into a time-honored genre.

***

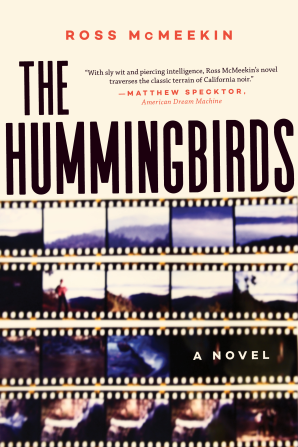

The Hummingbirds

by Ross McMeekin

Skyhorse Publishing; 256 p.

Benjamin Woodard is editor-in-chief at Atlas and Alice and teaches English in Connecticut. His stories have appeared in Hobart, WhiskeyPaper, Hypertrophic Literary, and others. Find him online at benjaminjwoodard.com or on Twitter @woodardwriter.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.