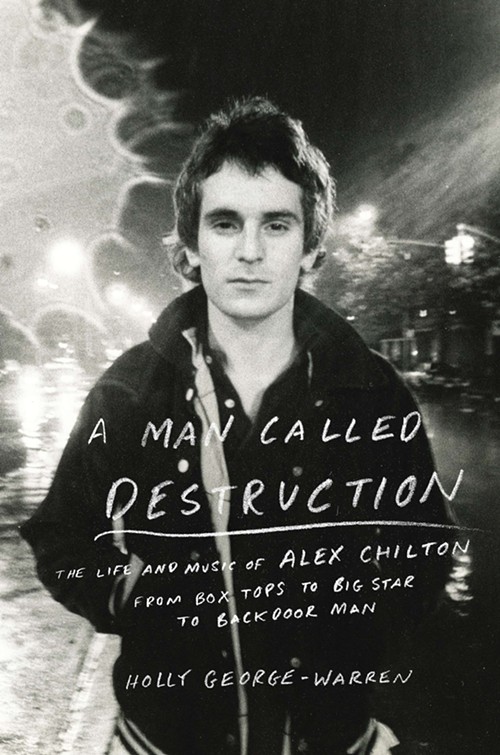

A Man Called Destruction: The Life and Music of Alex Chilton from Box Tops to Big Star to Backdoor Man

by Holly George-Warren

Viking; 384 p.

Though they’re often referred to as the definitive cult band, Big Star left the ranks of the obscure some time ago. The band’s story has been well told: A former ‘60s teen idol, Alex Chilton, hooked up with an old acquaintance from back home in Memphis, Chris Bell, to give the music business another go. A Lennon-McCartney-like synergy formed between the two, yet despite tremendous critical acclaim the band was a commercial flop and everyone left burned-out and disillusioned. Tragedy, in the form of Bell’s death, would precede redemption, but the band would eventually get its due decades later. Between a few books, a well-received feature-length documentary, a Grammy-winning box set, and a successful series of tribute concerts, the Big Star name and story are now as familiar as, at the very least, the Velvet Underground’s (with a similar adage about a scarcity of original fans all starting original bands applying equally to both). But while Lou Reed would become a bona fide rock star, albeit a complicated and cantankerous one, Alex Chilton would remain an elusive and enigmatic figure until his premature death in 2010.

In the appropriately titled A Man Called Destruction, the first book to focus specifically on Chilton’s entire life and career, author Holly George-Warren does an admirable job of piecing together a picture of a man whose seeming every decision was designed to confound and undermine the image others had of him—whether of a washed-up relic, a pop genius, or, as the book’s title suggest, a self-destructive waste. Through a variety of first-person interviews, press clips, and reviews, Chilton emerges as a true maverick whose ultimate fixation was not on finding success in the music business, but rather finding that success and a sense of personal contentment purely on his own terms—to become a “self-made man” as he once quipped about what he wanted on his grave.

George-Warren’s approach is straightforward and almost workmanlike, which doesn’t always make for the most gripping read, especially for the nonfan. A Man Called Destruction does, however, provide a fairly detailed account of Chilton that extends well beyond what people know and feel about Big Star. Born in Memphis in 1950 to a pair of liberal, artistically and musically inclined parents, Chilton was presented with freedom, culture, and open-mindedness from an early age. Leading figures in Memphis’s lefty art scene, Chilton’s parents exposed him and his brothers and sisters to musicians, intellectuals, and artists (including William Eggleston, who provided the cover photos for Big Star’s Radio City and Chilton’s debauched gem Like Flies on Sherbert) who stopped by the Chilton family home/gallery. The groundwork was laid almost immediately for the development of a self-sufficient, forward-thinking individual accustomed to getting his own way.

Chilton’s parents supported his aspirations with the Box Tops (his father, Sidney, even negotiated a larger cut of the band’s take for his son), and in doing so provided Alex with a blunt introduction to the vicissitudes of the music business. Though certainly green when he first cut Wayne Carson Thompson’s perennial smash “The Letter,” Chilton would quickly learn to disdain being the puppet for anyone else’s pursuits. In the case of the Box Tops, the master would be singer-songwriter-produce Dan Penn. The book makes clear that Chilton learned a tremendous amount professionally and creatively during this period, but it also proved the genesis of his life-long acrimony toward the music industry, not to mention his reliance on copious amounts of drugs and alcohol to mitigate his disenchantment.

In most accounts of Big Star, there are generally notable gaps between the end of the Box Tops and the formation of Big Star; and again between the latter band’s dissolution and subsequent reunion in the ‘90s. Yet it’s these periods that really give shape to the full life of Alex Chilton. George-Warren, to her credit, doesn’t give short shrift to these formative stages, and allows us a warts-and-all glimpse of how the world saw the mighty Alex Chilton, and, more interestingly, how he saw it in return.

Prior to joining up with Bell, Andy Hummel, and Jody Stephens to form Big Star, Chilton spent considerable time in New York City, crashing on couches, growing his hair, and shedding the prepackaged image he was saddled with in the Box Tops. He considered taking a stab at being a folk singer and also cut a series of tracks—ranging from blues to country to pop to folk—that showcased his stylistic range, but would remain on the shelf for decades. Chilton would return to New York after Big Star’s demise, and as with his first stint in the Big Apple, we see a laconic yet searching individual aimlessly and recklessly crafting a musical identity and then watching it crumble.

Big Star is often thought of as the quintessential American power pop band. Though certainly a fan of the British Invasion sound that so informed Big Star, Chilton was neither particularly interested in being Beatlesque prior to joining the band and was all but finished with the style by the time he had moved back to New York in the mid-seventies. The Big Star aesthetic, as constructed primarily by Chris Bell and bought into by Chilton, was as much a vehicle toward potential success for Chilton as it was a true calling. By the time he returned to New York in the late seventies, Chilton was far more interested in the blooming punk scene than anything related to the band that would forever haunt him. At this point, he had virtually abandoned the Big Star legacy in favor of deliberately ramshackle performances with intentionally under-rehearsed bands and filled with oddball cover choices. Chilton acolyte and dBs founder Chris Stamey recalls in the book one infamous show with Television’s Richard Lloyd on guitar, noting that “this may not even be music. But I’m watching something, two guys strung out with a drummer who has no idea what they’re doing.” This would form something of a template for his performances for many years to come, albeit with a steadily increasing attention to detail and precision. At the time, however, it would prove his undoing in terms of having a productive career in the music business. Chilton didn’t merely shed the guise of the pop genius; he incinerated it and smoked the ashes.

George-Warren packs her book with anecdote after anecdote of Chilton betraying his talent and potential, yet she is always quick to counter with another example of the genius that lurked beneath the loathing. Chilton is ultimately shown to be a man of many vexing contradictions, and not simply in terms how he approached his craft. During the recording of the first two Big Star albums, we witness an innately gifted individual pouring himself into recording pristine, meticulous pop, and then publicly disowning the music a mere few years later. Though often aloof and capable of extreme disinterest in those around him, Chilton would also foment drama with nearly every member of the Big Star world—from drummer Jody Stephens to the equally volatile Chris Bell to friend and engineer John Fry. An often cold and distant man who relied on astrological readings to get close to people, Chilton was also capable of violent outbursts, vicious put downs, and pure verbal provocation. In one notorious interview with Andy Schwartz of New York Rocker, the generally liberal Chilton went so far as to bait the journalist with tired anti-Semitic remarks, pontificating on the “Jewish mentality” and noting their “big influence on the media.” And his tumultuous, fiery relationship with longtime girlfriend and muse Lesa Aldridge (one of the “Two Sisters” of Big Star fame), as detailed by George-Warren, was a veritable case study in mutually assured borderline personality disorder.

While George-Warren hints that the death of Chilton’s older brother was the source of persistent pain throughout the musician’s life, a pain he perhaps never truly grappled with, there’s not a lot of pop psychology diagnostics here. One thing that she does make obvious, though, is the degree to which Chilton’s behavior in all its variances was exacerbated by serious substance abuse. Chilton was a voracious, unrepentant pill-popper and a glorious drunk. The controversial classic Like Flies on Sherbert wouldn’t have been as brilliantly shambling if he hadn’t been so completely wasted, and its safe to assume that the dark emotional depths navigated on Big Star’s Third were as much a product of barbiturates as they were Chilton’s creative synergy with producer Jim Dickson. But Chilton might have also achieved much earlier the contentment that so eluded him if he’d been a little more sober. There’s no judgment or chiding on the author’s part, rather Chilton’s latter years are the proof. It’s really at the stage when Chilton recognizes and grapples with his problems that the “real” Alex, like it or not, begins to emerge.

While there was a cold turkey moment, Chilton generally stopped drinking in the early ‘80s and switched from harder drugs to fairly steady pot use. What led to this push for a relative form of sobriety is presented here as having been triggered as much by a shift in his view of himself as a performer as by a need to get sober in any sort of clinical sense. Chilton simply wasn’t interested in the spotlight anymore. Like all of the choices he made throughout his life, on the surface his decision to kick was completely nonchalant. Defying all conventional wisdom about where and how one should tame their evil ways, Chilton moved to America’s good-times capital, New Orleans, to unwind. While he would remain a guitarist for Tav Falco’s Panther Burns, he would quit music and live a booze-free life of near total anonymity in the Crescent City for years. Scraping by as a dishwasher and tree trimmer, Chilton would also make a buck here and there playing in various dives in the French Quarter. Distancing himself even further from his Big Star past and returning to the American roots cannon he so loved, Chilton would become a remarkably proficient player in various style from R&B to jazz and even classical. There’s a breezy, relaxed feel to George-Warren’s descriptions of these lost years, and it’s evocative of Chilton’s disposition. He happily gigged as a side man, worked on his house in the Treme neighborhood, and produced bands like the Gories and Royal Pendeltons. The Big Star reunions are described in a fair amount of detail here, but they come off, for Chilton at least, as just another gig, no different (and maybe even less fun) than a Box Tops reunion.

Chilton died of cardiac failure on the way to the hospital with his wife, Laura. His last words were “Run the red light.” The final impression George-Warren gives us is of a man that for all of his cantankerousness, his amateurish tendencies, and his erratic self-destruction very much wanted to live. He liked the life he made for himself regardless of what anyone else felt about his existence up to that point. A Man Called Destruction doesn’t answer all of the questions that surround Chilton as an artist, and some will still be left to ponder along with Paul Westerberg whether “Alex was some brilliant chameleon or just a guy who fucking lost it real quick.” (As if Westerberg, frankly, is one to talk.) Of course, the idea that anyone would even feel the need to ponder such a question, or any other question about Alex Chilton, would surely make the man himself laugh, or maybe scowl, it would depend on your sign, really.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.