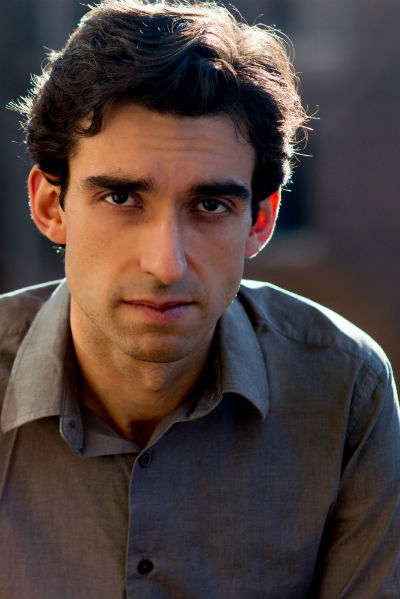

David Burr Gerrard‘s debut novel, Short Century, is a politically resonant work, revisiting national debates on war and morality that are never too far removed. At the center of the novel is Arthur Hunt, a liberal journalist whose politics prompted him to support the Iraq War. From the novel’s first page, we know that Hunt has been killed, and we know that we’re reading a kind of memoir, written after something scandalous has come to light. Through this narrative, a host of complex personal and political relationships are discussed, and it’s one in which few easy answers emerge. I met with Gerrard at Greenpoint’s Eagle Trading Company last week for lunch, where discussed the novel’s origins, his other works in progress, and the role of politics in fiction.

In the essay that went up recently on Biographile, you wrote about how your own political evolution shaped where you were coming from in the novel. Did you find that the process of writing the novel also caused your views to evolve in certain ways?

I was always immersed in Arthur’s perspective. While I was writing the book, he often convinced me of his positions. I consciously tried to make that happen. And it did happen, I think. Nothing is more boring than reading a book where you know that the author disagrees with the protagonist. I find that very dull, because you’re making up what the character is saying, and so you can make up any lame argument that you want to, or any lame perspective that you want to. That grows tiresome very quickly.

That being said, I would say that, as I wrote the book, I grew further and further to the left. By the time I finished the book, I really, really hated Arthur and everything that he stands for. I think that if I was to start the book now, the process would be more difficult, because I have less sympathy for Arthur than I did when I was writing the book. That makes me very glad that the book is done, because–like I said, I’m not interested in reading books by writers who have no sympathy for their characters. I’m glad that I had sympathy for Arthur while I was writing it.

For all that Arthur has views that could be called neoconservative, he also seems pretty idiosyncratic about certain things. There are characters who are much more pro-war than he is over the course of the book, and there’s the scene of the drone strike in the beginning, which shows where he draws a certain line…

I wouldn’t be interested in writing about a character who’s simply pro-war. Arthur’s attraction to war comes from humanitarian concerns, which continue to be occasionally attractive to me. When I read about what ISIS is doing in Iraq, I don’t immediately say, “No; America should have no involvement whatsoever.” We all want to save innocent refugees from what could be fairly reasonably described as evil terrorists. I don’t think you need to be a right-winger to use that term in this case. Nonetheless, if you step back and look at the course of history over the last several decades, you see that these good intentions that America professes constantly result in more and more bombing, more and more war. There was a piece in the New York Times a couple of days ago about the head of ISIS, and the way in which his imprisonment by America really would up radicalizing him.

There’s definitely the Samantha Power argument for humanitarian intervention–though that also ends up calling to mind the debate a few months ago, with Reihan Salam’s essay about why he considers himself a neoconservative and Tom Scocca’s rebuttal to it. Watching that debate unfold on Twitter, there were questions asked about where someone like Power would fit on that scale…

And, to a certain extent, these labels of “neoconservative,” or “left,” they serve some kind of purpose, as far as figuring out where people are. But there are also a lot of cultural reasons of why you’d prefer one label over another. I remember, in 2003 and 2004, a lot of people like The New Republic would call it “neo-liberal,” mostly because they didn’t like the term neoconservative. They wanted to think of themselves as liberal, rather than conservative. Trying to figure out how to engage with the world as a human being, certainly, you’re always going to have those labels.

There certainly seems to be a lot of Christopher Hitchens in Arthur Hunt’s DNA, but there are huge differences in his background. Were there specific writers and thinkers you were looking to for this?

Hitchens was a very big one. The other biggest one was Paul Berman. And then there were a number of other writers who had been 60s radicals who supported the war, not because they said, “We were wrong in the 60s and we’re both right-wing and correct now.” They saw the war as the fulfillment of 60s ideals: “This is a war for freedom. We’re liberating Iraq.” I was very interested in that idea.

In terms of how I married that to Arthur’s background… The genesis of the book is that I was working as an intern on the Howard Dean campaign. This was right after college. My job, which really seems ancient now, was to get up at four in the morning and cut out news clippings. Now, I’m sure, this is all done online. I would cut and paste news clippings related to the campaign. There were a lot of things on the candidates’ backgrounds, and a number of them had been at Yale in the 60s. Bush, of course, had been at Yale in the 60s. Howard Dean was at Yale in the 60s, Joe Lieberman was at Yale in the 60s (he was a little older), John Kerry was at Yale in the 60s. It occurred to me that this was incestuous. It was that pun that gave rise, in many ways, to the book. I wouldn’t recommend using a pun in general to start writing a novel, but in any case, that’s how it happened for me.

When I was interested in was: on the one hand, you have the Iraq War. People who were arguing for the war on humanitarian reasons were saying, “We’re transcending race. We care about the Iraqi people as much as we care about our own people.” On the other hand, it seems like there’s a certain strain of white supremacism in American culture, which you’re seeing very much on display right now with Ferguson. And the tension there was something that really interested me, and made me want to explore this theme of incest and ideas of militarism.

Has the feedback you’ve gotten regarding the novel, has it been more political or more literary?

I’ve gotten a lot of feedback from both angles. A lot of the people who have read it have been more interested in the literary side, but literature is always a little more difficult to talk about than politics. I’m certainly very happy to talk about the literary side as well.

In terms of Hunt’s history, you have parts of the novel set in the present day, focusing on Iraq and what comes next, and you also have him dealing with questions of his past. How did you find the balance between those two? Were there things that were cut out, or did you have a sense of what the proportions should be?

There was a huge amount that was cut out. The book took me, essentially, ten years. That’s a little misleading. What happened was, I finished–or thought I had finished–in 2008, just as Obama was getting elected. I had conceived of it as a response to the Bush administration, and I thought, “Oh, okay–Obama has been elected, and now all of this is irrelevant.” In retrospect, I was too pessimistic about my career and much too optimistic about the country.

After that, I spent the next three years starting my second novel, which I’ve since come back to, and reading unhappily about drone strikes and so forth. It was only in 2011 that I came back and finished it. I added the section that begins the book and the section that ends the book, and a number of other things. In terms of balancing the personal and political, that was very much a matter or trial and error. Mostly error. I wrote many scenes involving Arthur’s personal life that I jettisoned. He had a cousin, at one point, who was very prominent, who’s now not in the book at all. It would be interesting to do a survey of characters in drafts of novels who did not make it to the final cut. The balancing was very tricky. There was also a lot about politics that isn’t in the book. I didn’t want to write straight-up political essays. The scenes of people discussing politics, I knew, were going to be a major part of the book, but I also wanted to integrate them better into the story. I didn’t want to stop the action for a debate. Ayn Rand is a much more influential writer than I’ll ever be, unfortunately. I get bored with her books very quickly; I haven’t even finished any of them. And there are a lot of writers who I agree with, whose books I get bored with because the action always stops. I wanted the politics and the personal story to always go together.

When you wrote the introduction and the final section, how did you get the idea that Arthur’s story would be presented as a found manuscript, rather than simply a first-person narrative?

I always liked books that step out of their main perspective and shine a different light on what I’ve been reading. Even though I wanted to convince you of Arthur, and wanted to convince myself of Arthur, and wanted to immerse you in Arthur’s perspective, it’s also a very claustrophobic perspective. What happens with claustrophobic perspectives is that the reader can simply revert to the opposite pole, and think, “Everything this narrator says is false,” and that’s it. There’s one other character whose perspective is much closer to mine, but at the same time, I don’t agree with this perspective. I want you to wrestle with the perspective that you get at the end of the book, just as you wrestle with the perspective that you get throughout most of the book.

There’s an ongoing element in the book where a specific nation’s name cannot appear in print, and is only referred to as “REDACTED.” Did that come at the same time as the rest of the narrative, or was that written later?

That was what came in 2011. That and the blogger character, who’s hounding Arthur. That arose from a sense that we keep getting involved in these wars that we hear about, for a week or six months, and we never hear about these countries again. I wanted to evoke that on the page. One of the reasons why that country is referred to as “REDACTED”–in one way, it’s that country’s way of shielding itself from a Western gaze. Which seems to not necessarily be the worst idea in the world. We’re very much at war with Yemen and Pakistan via drones, and yet Obama keeps being referred to as a President who’s reluctant to take military action. He’s taking military action all the time, but we don’t have a sense of what’s happening in those countries. There are these long military campaigns; there are these flare-ups in various countries with various groups. We hear a lot about the Yazidis right now. How many people know who they were two weeks ago? How many people will remember who they were two weeks from now?

You were talking about your second novel earlier–is that also rooted in politics?

That novel is called The Epiphany Machine. It’s about a machine that tattoos epiphanies on the forearms of its users. That is my attempt to question and honor one of the major ideas of fiction, which is that fiction should lead up to an epiphany. That leads very easily to cliche; at the same time, I’m not very comfortable with total rejection of the idea of an epiphany. If fiction doesn’t force its characters into a realization of some kind of truth, if you don’t force the reader into a realization of some kind of truth, then what is fiction really for? My conflicting feelings about epiphanies drive that novel, just as my conflicted feelings about the Iraq War drove Short Century.

As to whether it’s about politics, it very much is. We are adrift in terms of what to value, and we’re very susceptible to arguments like, “This is the way that we should live right now.” The ideas of self-help have a lot of very complicated political ramifications that I’m using this book to explore.

You mentioned that you had cut a lot of things out of Short Century–do you see any of that returning as a short story down the line?

Last night, I was looking through some discarded material for The Epiphany Machine that was dated 2007. I didn’t even remember that I had started this book in 2007. It was a document that was 25,000 words long that I had simply forgotten about, and there was a lot of stuff in there that I could use. I have no plans right now to use the discarded material from Short Century, but: never say never.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.