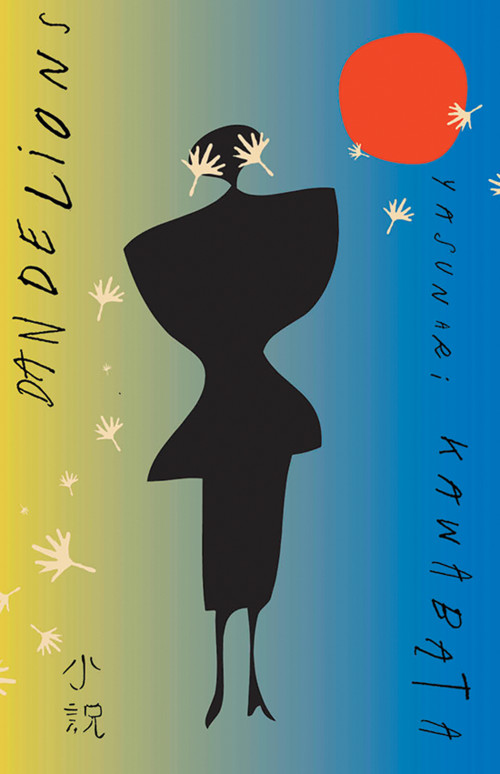

Dandelions is the final novel from Nobel Prize winning author Yasunari Kawabata. Though it was left unfinished when Kawabata committed suicide in 1972, it is a mark of the novel’s peculiar greatness that it does not feel incomplete; less polished in places, maybe, but aching throughout with the texture of dream. Dandelions is a beautiful work by one of Japan’s most celebrated authors, and we are fortunate to have the novel published in English for the first time.

The subject of Dandelions is a woman, Ineko, who suffers from a disease translated here as “somagnosia,” which means she occasionally loses sight of objects or people and sees only thin air where a moment ago there may have been a ping pong ball or her mother. Modern readers may recognize this disorder from the title essay of Oliver Sacks’s The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat, although Kawabata’s version is more severe. In Dandelions, Ineko’s disease is bad enough to require full-time institutional care, and the novel opens just as Ineko’s mother and lover (a young man named Kuno), have left Ineko at a place called the Ikuta Clinic in a valley filled with dandelions. Though Ineko will appear later in the novel in flashbacks, we never hear or see the institutionalized Ineko; she remains invisible to us, a reflection of her own disease.

Dandelions moves slowly, building its form entirely out of conversation between Kuno and Ineko’s mother. Their steady walk away from the Ikuta Clinic takes them through a range of topics, including Ineko’s childhood, the onset of her disease, and the two characters’ differing beliefs about fate. Occasionally their conversation is broken by oddities in the landscape—a white dandelion, a yellow little boy—but otherwise the prose flows easily between reminiscence and observation, quietly shaping a story about a girl who sometimes cannot see. The narrator speaks softly throughout, making his presence known with remarks like, “Bright blue flowers, small, ever so small—what were they called?—bloomed there in an unobtrusive way, like a harbinger of spring.”

Ineko’s admission to the Ikuta Clinic is not necessarily permanent, but since no one expresses any real faith in the possibility that she will be cured, her institutionalization feels like a kind of death. The slow departure of Kuno and Ineko’s mother from the clinic, punctuated as it is with visions of strange creatures and blurred boundaries, feels like a journey back from the spirit world. And when the doctor tells them to listen to the clinic’s bell and imagine that Ineko is ringing it, he may as well be telling the living how to best remember the dead.

This all forms a complicated elegy at the heart of Dandelions which aims at more than simple remembrance. Among other problems, the novel addresses the contradiction that to write about the dead is to enshrine yourself along with the departed. As Kuno says to Ineko’s mother, “I may be young, but I’ve seen a fair number of people die, people I was close to, and as a result of that, I suppose, I’ve come to think there’s something insolent in mourning the dead, tying death to oneself in that way.” Literature is indeed full of elegies whose subjects we have forgotten but whose authors we continue to celebrate: as James Schuyler begins his wonderful elegy for Frank O’Hara, “There is a hornet in the room / and one of us will have to go / out the window into the late / August midafternoon sun.”

Dandelions also silently evokes the many tragedies of Kawabata’s own life. Orphaned at the age of four, Kawabata grew up with his grandparents in Osaka. His grandmother died when he was seven, and his grandfather when he was fifteen. His older sister, whom he met only once, died when he was eleven; he had no other siblings. When Kawabata eventually accepted the 1968 Nobel Prize for Literature, he spoke at length about the prevalence of melancholy and suicide in Japanese literature. Two years later, his close friend Yukio Mishima committed ritual suicide. Two years after this, Kawabata took his own life.

There is a question in the novel of whether or not Kuno and Ineko’s mother ought to examine Ineko’s childhood for possible sources of her disease. Ineko’s mother primarily looks to the time when Ineko was quite young and her father went into the mountains to commit suicide. He soon returned, telling his wife and daughter that he was saved by a young girl, but Ineko’s mother doubts the girl’s existence, and a few months later, when Ineko is out riding with her father, she sees him ride off a cliff into the ocean. Ineko’s mother asks Kuno if this could have been the impetus for Ineko’s somagnosia, as if this early scene of death was now simply repeating itself, vanishing objects under the gaze of its survivor. Kuno disagrees, arguing that any number of causes could be pointed to, from the very instance when Ineko’s mother and father first met, to Japan’s loss in World War II, and that it is useless to try to determine a person’s fate in this way.

The debate between Kuno and Ineko’s mother reflects our own compulsion to find reason in death, especially in suicide. After Kawabata took his own life, a minor sensation grew out of an egregious little book called An Account of the Incident by Yoshimi Usui, which cited Kawabata’s spurned love of a young housemaid as the cause of his suicide. The book sold over 250,000 copies before Kawabata’s family successfully negotiated an injunction against its publisher. Of course, others seeking a reason for Kawabata’s suicide could look to his early experiences with loss, his Nobel speech on suicide, his paper on suicide entitled “Eyes in their Last Extremity,” the suicide of his young painter friend, the suicide of Mishima, or Akutagawa, or countless other writers. Or they could look to his work itself, as many have done, and find resonance in themes of melancholy, loneliness, and everlasting quiet.

In the absence of a suicide note, Dandelions does reveal a forceful occupation toward the end of Kawabata’s life with questions of remembrance and survivor’s guilt. Kawabata halted the novel’s ongoing serial publication after winning the Nobel Prize, and naturally there has been speculation as to the possible reasons for his decision. However, although Dandelions discusses suicide extensively, its main thrust is precisely against these attempts to understand it, to trace death to biography or history or psychology. As the novel progresses, and Kuno and Ineko’s mother walk farther away from the clinic, they grow more comfortable discussing Ineko in the past tense, while their own characters become stronger and physically present. When Kawabata ceased publishing Dandelions, we cannot know how he envisioned the novel ending, but in the version we do have its trajectory is emphatically toward the living.

At the beginning of Dandelions, we see an old man painting over and over again a line by the poet Ikkyū: “To enter the Buddha world is easy; to enter the world of demons is difficult.” The same line appears in Kawabata’s Nobel Prize speech, where he provides some further explanation: “For an artist seeking truth, good, and beauty . . . There can be no world of the Buddha without the world of the devil. And the world of the devil is the world difficult of entry. It is not for the weak of heart.” Dandelions walks us away from this world, showing a landscape regenerated through conversation and love instead of dissecting a mind gone astray.

***

Dandelions

by Yasunari Kawabata; translated by Michael Emmerich

New Directions; 128 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.