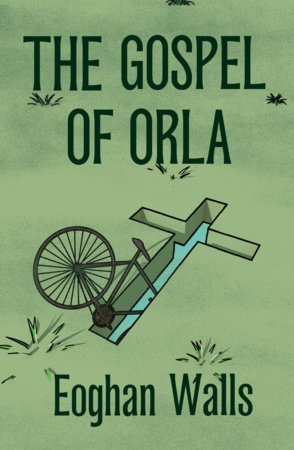

This recent novel by Northern Irish poet Eoghan Walls has an intriguing, Magrittian cover: it wraps around from front to back with a lively green backdrop, punctuated with sparse tufts of grass. Between the title and the author’s name on the front page is the 3D cutout of a cross. Unexpectedly, the cross is not centered and frontal, but slanted and on the ground, in the grass. Looking closely, it is possible to see a sliver of pale blue through it (another sky? another world?) and the silhouette of a bicycle entering it. I can’t think of a better way to visualize this enigmatic story. So much of Walls’ novel takes place outdoors, in the no man’s land that is the contaminated nature at the edge of urban areas; bikes are a big part of the action; there is a girl who metaphorically must carry a big cross of mourning and suffering on her shoulders and there’s a strange man who calls himself Jesus.