The Last Kingdom in Astoria

by Gessy Alvarez

I walk down Astoria Boulevard around six in the morning; the street is leading me to the chaos in front of the supermarket where I work. The lights in the neighborhood have been out for over twelve hours. I watch my moving reflection on the darkened storefront windows I pass. Back slumped forward. I look shorter than my six-foot frame. I look like a question mark. Greasy, black hair combed back – I am confused for Greek, Italian, Spanish, Brazilian, and sometimes Russian. But I’m not any and all those ethnicities. I was raised in Queens. I have no other history.

The coffee shop on the corner shut down two years ago. I don’t have a cup of coffee in my hand, but I do have a flask in my back pocket. Today, there will be a line outside the supermarket doors. The people will want to get their hands on all that’s left on the shelves. They’ll want the water bottles and sodas, the canned goods, the cereals, the bags of potato chips and pretzels. They’ll ignore the dairy and meat aisles. They’ll beg for the year-old bags of ice in the freezer. The lines to the cashier will stretch into the produce section. The fruit and vegetables will faintly smell of rot. We’ll sell the dairy, meats, and produce at half price. Those on public assistance will grab all they can. The old women will complain there aren’t enough cans of kidney beans or tuna fish on the shelves. The children will chase each other around the deli counter and hide behind the mob fighting over the last loaves of bread. I will roam around the store with the other store managers. We’ll wear our white coats still covered in yesterday’s grime and spoils. Like sergeants preparing for surrender, we’ll smile faintly as we try to appear like we’re in control. More than a few customers will end up shouting at us. There will be housewives trying to win our attention. They’ll flirt with us and ask for discounts off items with close expiration dates.

And the city is quiet this morning, Astoria Boulevard solitary. This street is a bustling, commercial enterprise on a normal business day — but it’s not a normal day.

Last night, from our sixth-story window, I watched the people coming out of their buildings, heard their woes and unease. My wife, Helena, and I had moved to Astoria ten years ago. Now she’s dead two years.

She’s watching over me, over us.

I can still see her serene eyes and awkward stance, avoiding attention, even as crowds of people flock around her on the boulevard. She slips through too shy to make eye contact with anyone. I saw her first in a frenzied fruit stand by the N train steps. She was smiling at the babies hanging from tired arms, and I thought I wanted to be smiled at too. She would love me, take care of me.

That was what I wanted. I don’t think I wanted to love someone back; I just wanted someone to love me. And she did love me and that was enough for her — at least until she gave birth to Mariss, and being a mother made her wonder perhaps if loving someone was enough for her.

But I couldn’t love her back. I wasn’t happy when she became pregnant. I was ridiculous and fearsome. But, when she gave birth, I changed. And when she told me she had cancer, it was the one and only time I loved her. Or, at least, I believed I loved her. Mariss was 14 when her mother died.

I tried to mimic the ease in which Helena cared for Mariss, the peculiar giving and nurturing, which felt too foreign, which made her a good mother, patient, so generous to her daughter, without question or doubt. So different to what I gave because it was not demanded of me to give but to perform my mechanical duty. This life we had to act out under the watchful eyes of working-class families flourishing in Astoria, with rules to follow, and tradition—it was tradition that failed us – because to conform is to control life.

Helena left me with a daughter, but you can’t force someone to stop fearing the chaos of life. The more responsibility you are given, the more you want to control and make sure bad things don’t happen. Life gives and takes away. There is no control.

I was drinking beer, when I told Helena she was the love of my life. Nothing as devastating as her illness had happened to us in the 15 years we were together. Nothing she never forgave and I forgot. Not even the other women whom meant nothing to me, whom I walked home and whom I let pull me inside strange bedrooms.

Now, it’s dark again, no lights outside except flashlights and lanterns, no matter how fast we tried to sell the rotting fruit and vegetables, the stench and waste engulfs the store. Boxes of decay are stacked out front. Juice and slime stick to the tile and streak the sidewalk. I shall never find someone to love me again. These days’ women are too busy to stop what they’re doing and take care of me. I can’t love them back. I can’t be trusted.

If this blackout never happened, if Helena hadn’t died, if I were a better father, Mariss would love me. My daughter would take care of me, but she left the apartment last night and she never came back home.

___________

I’m sorry now, not that it does any good, sorry for not being up front with my wife, the one person who deserved my honesty above anyone else. Helena never bought any of my bullshit that I never slept with other women, I had and did often. But those last days two years ago, I promised her that I would honor our marriage vows even after her death.

The last woman I had was about my age, give or take a couple of years. Her name was Doris. She was smart, a small business owner, independent and had a lilting laugh. I used to buy my morning coffee and a newspaper at her shop. She asked me about Helena, and when I spoke of the cold sweats and anxiety that kept Helena up most of the night, Doris would pat my arm.

I ran into Doris at the bar near the supermarket one night when I felt like staying out late. I had lied to Helena. Told her I was taking inventory all night. Doris’s mother had recently died of complications from pneumonia and had left Doris a small inheritance. That night she treated all nine of us inside the dive bar to drinks. When the construction workers stopped in before their early morning shifts, I held her arms down before she could order another round. “No more,” I said. “These boys will burn through all your dough, and then what?”

She looked up at me as I crowded around her and nuzzled my chin. “You’re a good apple,” she said.

And I think around two or three in the morning we left the bar together. I know that I felt lighter as we traipsed around the sleeping neighborhood, teasing each other with talk of our past sexual misadventures—stories I’d never told my wife but which I felt mysteriously comfortable reciting to this stranger. I remember not wanting to stop talking to her. I blamed it on the shots of bourbon and the balmy night. We walked towards a destination. We slipped off our shoes and crept up the narrow stairs to her second floor apartment in a two-family house. We shared a cigarette, the trapped smoke overtaking her tiny kitchen, and we drank orange juice straight from the container. We must have kissed at some point, I can’t think of how she became comfortable enough to sit on my lap in the middle of that tiny kitchen. I remember sliding my hand over her hip to keep her there, her shallow breath hitting my forehead and her lips touching my brow. The low sound of her landlord snoring in the apartment below, of her whispers and of my panting, it all felt right that night and I was so grateful to be with her.

When Doris stood up, we looked at each other; all other noises stopped. We stepped quietly through the living room, into her crowded bedroom, undressed at the foot of her queen-size bed, and slipped under a crocheted blanket her mother had made. I fell asleep for some time, I think. But she woke me up and caressed my stubbly face.

“What?” I said.

“You fell asleep,” she said.

“Sorry. Long day.”

“I think I bored you.”

“Don’t take it personally.”

Doris looked at me and waited. It was as though she needed my permission to continue. I laughed and slipped my arm under her waist and nuzzled her breasts. I played with her, but when I kissed her neck she squirmed away from me. Something happened in her and in me. She did not resist me, she lay there and waited. And I realized that I couldn’t take a deep enough breath and that she trembled beneath me and that the orange street light was too harsh, too bright. I started to move, to make room between her legs. She lifted her head and kissed me. For the first time, I was aware of lips against my own, of someone else’s taste. I squeezed her ass, her shape slighter than Helena’s, her hips narrower. I didn’t want to hurt her as I pushed inside her. To remember that moment so vividly, so crucially – I changed that night.

I feel a faint guilt, a dreadful remorse of how free I felt. How my thirst for escape was quenched for a moment. But from this guilt came release; we let ourselves go that night. It seemed like we would never get enough of each other. I squeezed her hips, dug my fingers into her flesh and heard her tiny yelp, but she didn’t push me away. Her small hands ran over my back, her nails stabbing the right pressure points. When I came I bit down on the flesh between her neck and shoulder.

But by morning, the need to bolt, to pull away from her shook me awake. She slept on her stomach. She looked like a limp marionette, her red hair fanned over her creased cheek, the gray roots more apparent in the morning light. I looked around the room for my clothes. My shirt hanging off the foot of the bed, my pants crumpled on the floor, my underwear on the nightstand. Doris snored softly, her pink lips slightly open, the sheet covered most of her pink flesh except for her left shoulder and arm, which hung off the bed, short fingers brushed the floor. She was not young or beautiful. But she was real and the soft sounds that came out of her made me hard all over again. I would have slipped back in the bed with her but I needed a shower. I needed to get home. Perhaps it was because she looked so warm and soft in the bed, peaceful; perhaps it was because she was so different than me; I was rough with her last night, she would see my mark on her hips and the back of her thighs.

She is not your wife.

The life and promise and power of her body terrified me. Doris’s strength offered me a sharp contrast to what I no longer had at home. I ran my sweaty palms over my hair. I had a sick wife waiting for me and I was ashamed. This sweet woman was the devil tempting me away from my family.

Then I thought about the neighborhood and how we would see each other on the streets. A hole opened, deep and bottomless. I thought about my daughter and how she would lose her mother and I would be her only family, except for her aunt who hated me. The hole and our future buried in darkness, full of regret, self-loathing, of empty endearments, exaggerated memories of Helena as saint, angel, good mother, loyal wife. I thought of falling into the hole, losing myself in it. I was terrified of the blackness. I could have screamed, screamed my terror. But I left Doris in her warm room.

I stopped going to her shop for coffee. Instead, I walked three blocks in the opposite direction from the supermarket and grabbed coffee from a food truck. I didn’t see Doris on the street. She seemed to avoid me too. I didn’t like making her uncomfortable. If I had seen her, I would have greeted her, but I had abandoned her. When we did meet later that summer, on a street a few blocks away from the supermarket and her shop, on a hot July day, I said hello and apologized. She didn’t say much and I lied, said I was late and needed to take Helena to her doctor’s appointment in midtown and when autumn came Helena refused to get up from bed and stopped going to her appointments altogether.

Doris closed her shop a week after Helena’s death, moved to Florida. I never saw her again. I mourned that winter for my wife and retreated from my daughter.

And still – I searched for solace, for a warm body, for the weight that would bring comfort despite my apathy, through false desires and phantom lust, the doors to love closed. This blackout may have begun last night, but my troubles with Mariss began after Helena’s death. As I now walk home down streets lighted with flashlights, passing neighbors sitting outside on milk crates, complaining about the City, the Mayor. I listen, unable to speak my fears, my frustrations, and my failures – unable to scream of my daughter’s disappearance.

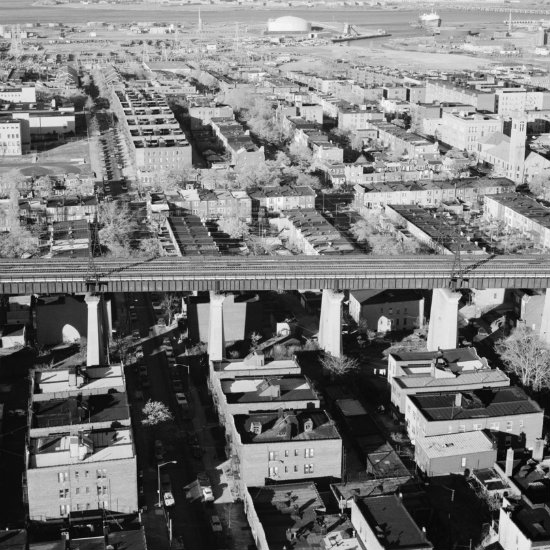

Gessy Alvarez is founder and managing editor of the literary website, Digging through the Fat. Her short stories have appeared in Entropy, Drunk Monkeys, Extract(s), Literary Orphans, Bartleby Snopes, Thrice Fiction, Pank, and other publications. Her first novel, The Last Kingdom in Astoria, follows a widowed father and his sixteen-year-old daughter during an eight-day blackout which affected Astoria and other parts of northwest Queens in July 2006.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

1 comment

Now The Last Kingdom http://imgur.com/zB3mhQd/ full new episode