American Smoke: Journey to the End of the Light

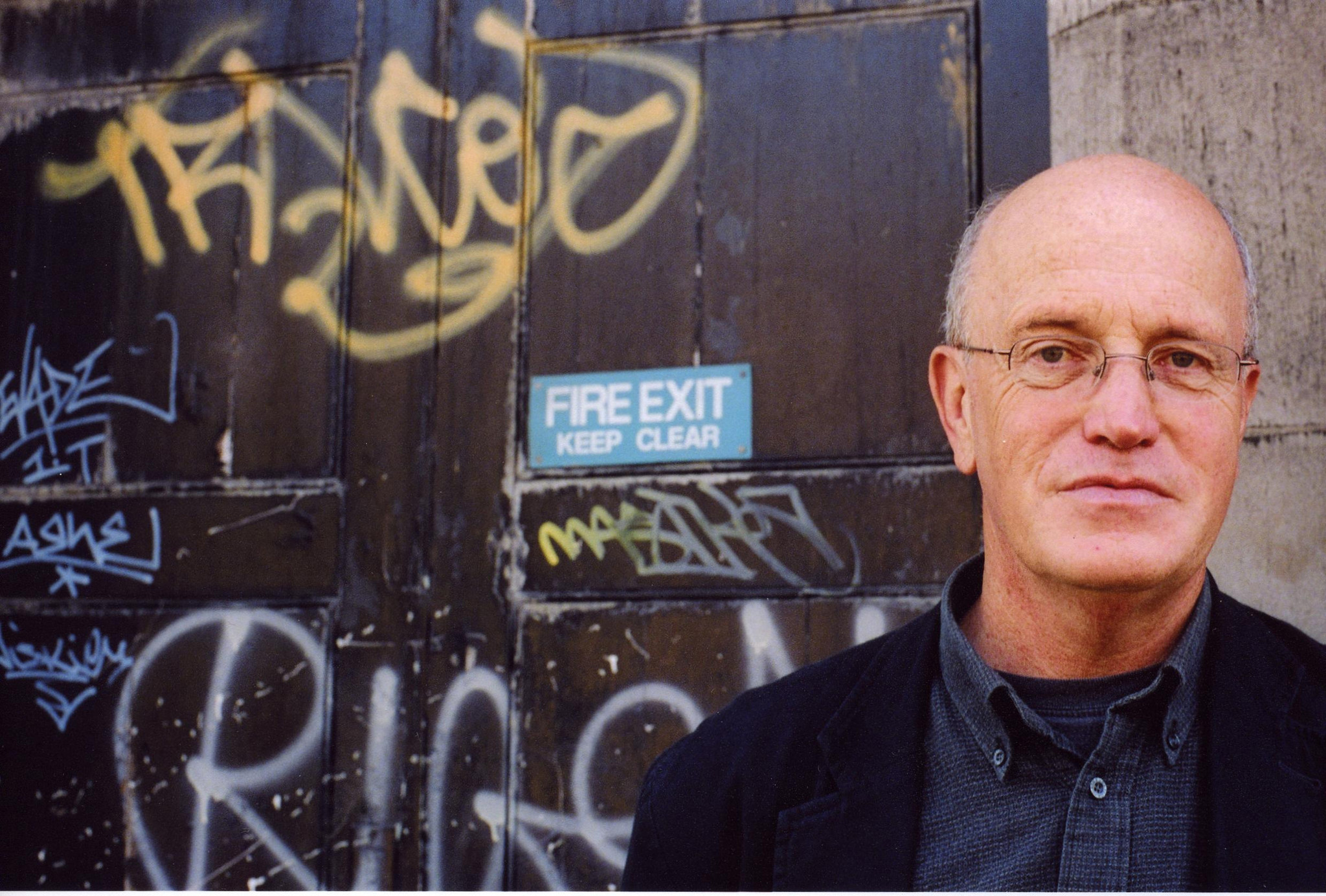

by Iain Sinclair

Faber & Faber, 320 pages

Iain Sinclair is a psychographer, a term he eschews, but reading his work is an experience that goes beyond the implications of that word. In American Smoke: Journeys to the End of the Light, Sinclair follows the footsteps, sometimes real and sometimes imagined, of great counterculture figures of the Beat Generation such as William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Charles Olson, Malcom Lowry, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Gary Snyder, among others, and explores their interaction with and impact on culture, art, place, and himself.

From a critical standpoint, Sinclair does everything wrong. However, he somehow manages to get it right. For starters, this is not a memoir, travel book or purely academic collection of biographies. Instead, American Smoke offers a series of essays that walk the line between a plethora of genres, mix historical facts with beautiful poetry, and repeatedly ignore chronologic order. It probably sounds messy, but Sinclair weaves everything together in a cohesive way, so no shift in subject or change in time strikes the reader as abrupt or jarring. Besides these perennially shifting elements, the author possesses an intellect that rivals those of the brilliant individuals he writes about, and he used it to construct a richly informed narrative chockfull of references that range from the obvious, like the book title’s play on Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night, to the downright obscure. Surprisingly, despite the lack of linearity and the fact that Sinclair’s intelligence and superb research skills can make the text intimidating to the uninitiated, American Smoke is an entertaining and informative book that at once celebrates and humanizes the larger-than-life figures Sinclair dissects.

Anyone coming into a tome about the Beat Generation probably knows something about its most renowned writers. While this familiarity comes in handy and helps the book set its hooks in early, American Smoke is a strange and unpredictable read because Sinclair’s brings together key figures of the Beat Generation and interweaves their stories with those of the places in which they worked, his own thoughts, memories, and feelings, and tangential narratives about the people who surrounded their lives. This is a fragmented autobiography of Iain Sinclair as much as it is a book about the Beats, pop culture, movies, travelling, Olson’s Gloucester, Burrough’s Lawrence, and the secrets, lies, and half-truths often found when conducting research on famous characters. The result of this wild mixture is a multilayered text in which names like Ginsberg and Kerouac end up intermingling with others as unexpected as Courtney Love and Aliester Crowley.

Sinclair never pretends to hide himself in the narrative, and the narration and descriptions are better because of it. Also, one of most interesting things about the book is the way mythical figures are deconstructed and either emerge from the process unscathed or suddenly acquire flaws in the author’s eyes that are not unlike cracks in a statue. Ginsberg, for example, does not survive the scrutiny intact:

Ginsberg had perfected a repertoire of standard anecdotes, a constantly revised history —with a hot fix of recent, excited, all-night conversations with Olson, Burroughs, Panna Grady. To which he now added the sight and odour and touch of those great manipulators, the millionaire rock stars with their willingly seduced multitudes. He huddles with McCartney; he tries to teach Mick Jagger how to breath. Celebrity feeds on celebrity in a cannibalizing ring fuck. Morning interviews, squatting on the grass, hold up the party. Ginsberg is a vampire for fame, immortality.

On the other hand, the legendary Burroughs, who was already a walking ghost much greater and infinitely weirder than the flesh he occupied years before his death, acquires otherworldly powers as Sinclair spends time with him:

Burroughs is courteous, he responds, but he is not really there. Without moving his lips, he dictates the script. You find yourself ventriloquized by texts he has not yet composed or will never compose. The skin is made of a kind of liquid glass. Gazing into those mercury eyes, you are looking at a marmoreal version of your future self.

Sinclair writes about people and their work, about the way they connect(ed) to others and to their surroundings. He also writes exceptionally well about places, both real and those filtered through memory and lore. He creates a collective memory/consciousness in which Gregory Corso keeps his insane coolness and science fiction master William Gibson is capable of moving through airports “with such familiarity that he barely registered on their surveillance systems.” American Smoke is a book of personal and shared stories and histories. Sinclair has been in contact with the folks he writes about for a long time, and the effect that has on his writing is something he hints at while seemingly addressing life in general:

At a certain point in the journey of any life, a home is curated; it becomes an occupied memorial to dispersed family and friends; a museum of loneliness decorated with photographs of dissolved beings, paintings keeping rectangles of sunlight away from fading wallpaper. Votive objects achieve status only through our long engagement with them.

With its brilliant, feverish prose and the passion Sinclair shows for travelling to the heart of the Beat Generation regardless of how the trip affects his ideas about the era, perhaps this book’s greatest achievement is demonstrating that its author deserves a place among the literary luminaries he writes about.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.