The Weather of My Youth

by Michael Stutz

My Kurt Cobain moment happened only months before he died — Halloween night in the last October of his life. They were playing Rhodes Arena, the big concert hall at the University of Akron. We didn’t know it then, but Nirvana was on its final tour. They came out on stage in costume: Kurt was dressed like Barney, the big purple dinosaur for kids. Dave Grohl was a mummy behind the drums. Krist Novoselic painted up his face like some kind of weird mime and Pat Smear, the new guitarist, pretended to be Slash.

The weather was crazy then. The summer had been long, and that night a massive storm dumped a heavy load of snow upon the world, as if the autumn hadn’t even mattered. Even before the show it was already in the air — you couldn’t see it yet, but there was a steep change in pressure you could feel. It was almost too warm, the night too clear; far winds were coming and the years were dripping out their days too quick.

There was a mosh pit at the show, of course, but that was only for the kids and absolute outsiders — all the beleaguered veterans of mosh pits rolled their eyes and stayed away. These were changing times. We were all feeling older now, and our band Nirvana was a supergroup, no longer our own little secret that played on college radio. They weren’t underground at all — they weren’t even “alternative” anymore. At this point they were on top of everything. So technically, we had won. The revolution, or whatever it was that took our generation out in a single, broad tsumani wave in ’91, had finally been conceded us — but even so, one could not deny a sense of bitterness and loss. I was guilty of this disillusionment myself. I went around saying how I refused to see or even follow them, they were way too big — I accused them, in a sneer, of completely selling out.

This attitude was typical of those in my position. As a rock journalist-in-the-making it was my somber duty to evaluate and call the shots. The rock scene was our life, and the bands spoke to us in the language of the prophets. We knew all the songs; the music was our sweetest prayer and poesy. We thought the bands would save us. But we were kids ourselves, and hadn’t found our own way in the world — I hadn’t yet made it through the great gray mazes of Manhattan, hadn’t really gone anywhere on my own; even the whole West Coast was just a TV image to me then.

Volunteering for the college paper and then the local free arts weekly meant that I was ushered in wherever I wanted to go, for free, and appearing backstage after shows was as smooth and natural as stepping into my bedroom at my parents’ house. If I liked a band, it wasn’t long before I’d be hanging out with them. And so it’s easy now to reimagine a goodbye that Halloween night, even though I realize what it comes to: just a passing moment in our lives when we stand together in a room.

Looking at it now, the whole thing plays over and over in my head, like a homemade YouTube clip. We’re backstage, in a place of painted cinder block that seems to serve multiple functions — there’s couches, metal coat racks wheeled up against a wall, and it’s lit by rows of schoolhouse fluorescents so you can’t sense the time of day. The rest of the band are over by the food tray along with someone from The Breeders and a few other media people who had passes. In the hall is the steady, scraping bustle of the road crew, older guys who are wheeling out the speakers and the boxed equipment.

This is the moment I am standing next to Kurt. That’s when I say to him, “You are my brother.”

He’s all sweaty and tired from the show, and he’s quiet, doesn’t even say hello, he just takes in what I tell him. I’m not sure he gets it, that I looked up to him like he was an older brother; maybe he gets it even more than I do. But he doesn’t say a word. He just stares. Our eyes are locked. I’m a kid and he’s a man and everything is moving quick — yet revisiting that YouTube clip again I’m surprised to see he’s almost that much a kid as I am.

“What’s your name, brother?”

“Mike.”

He’s pensive, like he knows there isn’t time, and as if to recapitulate this fact some people start calling for him now — his tour handlers want him on the bus. Someone else is talking excitedly about the snow. His hand is on my shoulder now.

“Goodbye, brother Mike.”

On YouTube, my own hand is resting on his shoulder at this moment, too.

“Goodbye, brother Kurt.”

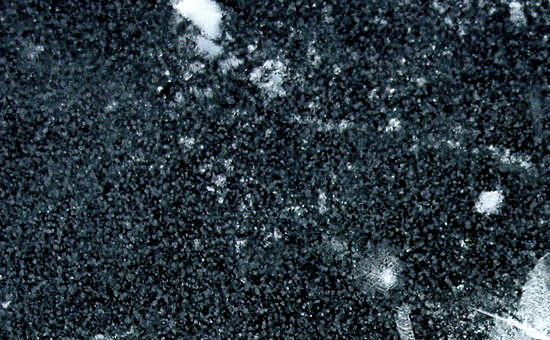

And then that world is totally erased, covered up in white. It’s more than an hour after the show and almost nobody is around; the mammoth noise of the concert is replaced by the quiet and the darkness of the night, mute fields of brand-new snow. You can see the fury of the storm at points in the coppery glow of the high-pressure sodium street lamps. To drive in it is like voluntarily diving headlong into a surrealistic dream: besides the salt trucks spitting coarsely on the road in front of you, there’s nothing — just the blinding, silent fury of the snow.

In the safe darkness of my bedroom, I think of Kurt my lost brother, sleeping on the tour bus as it’s cutting through the wall of spilling flakes in a far and unknown country, never to return — as if all of us really were strangers in this weird world, unable to connect outside these tiny haunted dreams.

A few months later, on that Friday afternoon in April, I got the call that he had died. It was a chunk of ice pressed suddenly to my back. I couldn’t say anything in reply — my lips, my tongue, my jaw, my whole body had gone immobile. All I could do was stand there holding the phone. For five minutes I was a statue, as frozen and as sudden as that October snow. It’s twenty years and I still can feel the way that it began to melt.

Michael Stutz is the author of Circuits of the Wind — a three-volume novel about the net generation — and is a former rock critic.

Image source via Creative Commons.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

1 comment

Thanks for this story – it’s chilling, no pun intended!