The concept behind the anthology Hair Lit is simple: writers (including Roxane Gay, Leni Zumas, and Lindsay Hunter) looked to hair metal songs for inspiration, with the results ranging from the absurdist to the grittily realistic. We’re happy to present one of the collection’s stories: Steve Himmer’s “Hard K,” inspired by Scorpions’ “Still Loving You.”

Our Man stands in a line so deep you can’t see what it’s for, maybe potatoes or bread or paperwork for permits to stand in more lines later on. But he knows what it is because he’s waited in this line before.

Here we go again, Our Man thinks every time someone advances, the left behind workers shuffling a few steps forward with shopping bags and attachés and rolling suitcases shoved along the train station floor by their feet. He’s still three passengers away from the folding table and the state police behind it in peaked hats that rise above the crowd like ICBMs nosing out of their silos. Our Man wonders, sometimes, about all those silos and what they’re holding these days, all that empty space underground like the nation’s gone hollow. He knows it’s not like that, he knows those dark chambers are a minuscule percentage of the country’s landmass, insignificant considering all that’s still solid, and yet… He doesn’t lose sleep over this like he did when he was young and those silos were full and expected to fire at any moment, but he worries when it crosses his mind and it’s a new kind of worry, less solid than at least knowing what he was worried about.

Would-be passengers wait in two parallel lines to step up to the table, to hand over their bags and to watch blue latex gloves swipe the handles and zippers and flaps with some kind of wet nap then scan the wipe in a machine that looks like the ones used to read election ballots and grade exams. The kind of machines that get results.

It’s a bomb sniffer, but Our Man doesn’t know quite what his bag and the others get tested for — Residue of gunpowder? A dusting of fertilizer and ammonium nitrate and anthrax, all those words that used to be specialized and are everyday now? He only knows the machine and its operators are here in the station one morning every few weeks for a random inspection, and his commute is disrupted those days. His mornings are science, down to the second: his shower, his coffee, his walk to the bus stop and a bus reaching the station with three and a half minutes until the next train. It’s rote, years of ingrained routine, and most mornings he makes it from his house to the desk in his office before he has to think, really think, because everything is in its right place. These inspection mornings, these interruptions that make him attend to what he’d rather ignore, knock his day for a loop.

The woman in front of him sets down her enormous brown purse — big enough to contain his own satchel two or three times — and crouches to rifle through it. She moves things around inside the bag without really opening it, working her hands blindly in its recesses like she’s hiding the contents. Our Man scolds himself for being suspicious, but when she takes something out — something small, a flat plastic case of some kind — and slides it into her pocket, he wonders if he should speak up. Or if he’s assuming the worst and would only delay himself longer while the police sorted out what is probably nothing. What is definitely nothing, most likely.

The line moves forward without her. She’s a small woman, low, in clothes that look fourth- or fifth-hand and years old, and Our Man could almost step over her back to take her place in line while she rummages but he doesn’t. He wouldn’t, though he imagines the look on her face if he did and the scolding he’d get. He’d be sent to the back of the line to start over, or he’d be sent home for the day, so it’s better to follow the rules and everyone will get where they’re going and stay on their routine, or stay as close as they can on a day that’s already disrupted.

He checks the clock on his phone and the one overhead on the red digital scroll that will announce the next train to the station. The other line is still moving ahead, half a table away; it’s making progress, and he kicks himself for choosing the line he did: it looked fast, efficient, no child holding a parent’s hand to create distractions and cause delays, no couples or pairs of friends too busy talking to keep up with it. No tourists who’ve never seen a subway before dragging huge piles of luggage one bag at a time like dazed refugees with all their belongings. His line had looked good and though he paused for a second upon entering the station — first to realize with a weight in his gut it was inspection day, then to calculate the odds before joining one line or the other — he’d felt confident as the first passengers advanced before him, because his line was outpacing their rivals. Two lines might look the same, appear equally equipped to reach the same point, but there’s always a difference and you need to get yourself on the right side. A day is built on choices like that, a moment lost and a moment gained, a crack in the sidewalk stepped over and a broken arm dodged, and a life is made up of those moments.

If you choose wrong, or if you don’t choose and get stuck in a line you don’t want, you’ll never switch from one side to the other without drawing reproach — Our Man has seen it happen, but never to him — from the police in their gun belts and badges. Worse are the dark eyes and ire of other passengers waiting, the death by a thousand stares, when they catch one of their own trying to get away with something. When they catch you thinking your time is more valuable and its waste a greater loss than their own, those eyes will haul you back into their ranks.

The clock crawls faster than the line does as that woman’s bag reaches the table at last and has its handle swiped, its wet nap scanned. The officer doesn’t ask about what’s in her pocket and doesn’t open her bag for a look at the makeup or cereal bars or pipe bombs or whatever she’s hiding and Our Man doesn’t say anything. Then she steps away and Our Man lays his own bag on the table — it’s already in hand, hoisted and poised to be in front of the officer even as he steps up, to save time; Our Man has done this before — but there’s a rumble downstairs as his train rolls into the station on time.

The officer has trouble opening the wipe; its foil packet tears but not enough, and he laughs the slow laugh of someone who can’t be hurried, at least not by the people around him who aren’t wearing gun belts and high hats and badges. It’s the laugh of someone who can make others wait, who can disrupt routines not his own. Then the bag’s handles are wiped, the bag is returned, and Our Man is rushing through the turnstile that’s no longer a turnstile.

The rolling metal rods he’d known all his life until a few years ago gave a reassuring kerchunk as they dropped into place one passenger at a time with a weight your whole body felt so you knew which side of the wall it was on. Now there are silent, sideways gates instead of those rods, plastic doors triggered by the almost inaudible tap of a plastic card on a plastic sensor instead of the rattle and clank of brass tokens the whole city ran on before, and people punch holes in those tokens and make them into earrings and key rings and pendants because they’re worth no more than memories now. As obsolete as the Soviet army pins our man collected in high school, pinned to the lapels of a denim jacket like everyone wore, weightless insignia no one can read. And now every part of those gates is replaced but the word; they’re still “turnstiles” in the recorded announcements that play on an overhead loop in the station, or if you ask the token sellers who are “ambassadors” now that their tokens are gone and diplomacy their last resort.

They’re ambassadors of no country but the checkpoint of not-quite-turnstiles where nobody stops, a place that is only the rush of its border no matter what people do on either side. A country with no culture but the culture of anonymous coming and going where everyone could be anyone.

What kind of country is that?

But Our Man has no time for postcards or photos in that strange land as the turnstile border slides open and he rushes across. He runs down the stairs but the train doors are already closing and he reaches the platform just in time to enjoy the smirks of his would-be fellow passengers already inside. The train starts up slowly and as it slides away he gets to enjoy those smirks for three or four cars before the faces speed into a blur and leave behind only the stragglers, tugging their collars against the cold wind of departure.

The woman with the enormous bag is there, too, clutching it to her scrunched body with both arms as her eyes dart around. Our Man looks up to where he knows there’s a security camera and it’s pointed at her. So if there’s something to watch, it is being watched. Somebody else is keeping an eye out this morning from a room in the depths of the station and Our Man needn’t worry himself. The system is working today.

But the poster across the tracks from the platform, across from where he stands, insists in big letters SEE SOMETHING, SAY SOMETHING and he wonders if it means him. If it means now, this woman, her bag.

From the other end of the platform music starts up, or maybe it was there all along behind the noise of the train. It isn’t the usual solitary saxophone player but a bluegrass trio of banjo, fiddle, guitar. The opening notes are familiar but he can’t place the song; he knows he’s heard it but not like this, not on these strings. Our Man will be waiting five minutes until the next train so he might as well listen. He might as well walk away from the woman, the poster, the bag. A guitar case lies open in front of the trio, and a sign propped against it reads Lonesome Crow.

The platform is eerily empty, like a scene in an old spy movie when suddenly, for no reason, everyone is gone from a place that should be crowded except for two agents meeting to exchange microfilm in false teeth or codes in the heel of a shoe or a nod on which World War III hinges. There’s only Our Man, and the band and their slow, ringing notes, and the woman with her bag farther down, though he’s sure there were others left behind on the platform and still rushing downstairs when the train pulled away. Maybe they’re waiting behind the elevator shaft or on the other side of the wide bank of stairs or are otherwise out of view, but it feels empty enough all the same.

Then the introduction hits the melody and he knows the song, his whole body knows it’s that Scorpions song that played over and over on rock radio when he was a kid, up late after bedtime and under the covers listening to Top 5 at 10 when those underground silos kept him awake. He remembers the video, the earnestness, the wide-stanced guitarists and the way their singer, the little guy, Klaus something or other, always hit the final G in loving like it was a K — I’m still lovink you — and how the blond guitarist picked up his note and made it wail as the camera zoomed in. He remembers that radio, a gunmetal gray boombox with all sorts of mysterious buttons he could make up uses for when he played secret agent — sneaking around the house, going through the papers in his father’s desk, cutting peepholes in newspaper pages to spy on his sister across the breakfast table. He needed a place to stash the codes he snuck out of the Kremlin, Our Man did when he was Our Boy, and he dropped them inside that boombox so it rattled ever after when a song hit a low note and shook those tight rolls of paper never retrieved by his counterpart from a country that no longer exists.

That hard K, like a wall between past and present for those young German lovers, concrete and barbed wire and rotating spotlights between being together and coming apart. It’s sad, but you know why you’re sad and you know what you’ve lost and when you lost it, you know everything but how to get back to it now. Maybe it was difficult but it was familiar and there was always a chance, always something to look forward to and you knew what that something was.

The fiddle crescendos into the chorus and echoes the length of the station while the banjo and guitar whirl and rattle behind—jubilant, bouncing, so much faster and less somber than he remembers the song but nostalgic the way bluegrass is. Not bad, not off-putting, but this trio has made something strange of it. Or it’s the askew combination of their unexpected arrangement and his own almost muscular memories of how the song goes.

The woman with the bag looks up at the camera then shuffles sideways without shifting her gaze until she’s put a thick cement column between its eye and hers. She’s crept closer to where Our Man stands but he turns from her and faces the music, knowing the guitar solo is coming except that it never arrives. Instead the violin — the fiddle, but that sounds so other than German — dances a jig or what he thinks a jig sounds like then that Irish bit morphs into a Russian folk dance then something he thinks is a theme from James Bond is followed by several quick snippets of other tunes one after the other. One is a nursery rhyme and another a pop song Our Man couldn’t name but has heard recently bleeding from headphones too loud on the train.

The guitarist and banjo player are laughing, almost cracking up. The rhythm is coming undone as the fiddler surprises them, too. But the three of them pull it together, slow down through the bridge — Our Man pictures a K knocked over sideways so it would form a bridge instead of a wall — and build toward the last chorus he remembers with every muscle like he’s heard this song every day, all his life, because it’s in his pores the way songs can be when you’re young. When a rock song is a real way of knowing the world.

The woman plunges one hand deep into her bag like she’s remembered something important, like it’s a rush, and she must be holding something in there because the bag hangs suspended in front of her body.

A gun? Our Man wonders. A bomb? And he hates to think that way, he hates to assume, but isn’t that what he’s supposed to do now? Our Man can’t wait for Soviet paratroopers to fill the skies of Colorado before he knows the invasion is coming; it doesn’t work like that any longer, the invasion is already here, from all that he’s heard: it’s everywhere and nowhere at once. It doesn’t follow the firm lines that a wall or even a curtain would keep.

Instead of winding down the way that song usually does, the band goes wild on the last lines, and it’s instrumental but Our Man remembers those repeated lyrics: I need your love, a few times, while everything fades.

Something firm. Something clear. An attainable desire the achievement of which can be measured: either he’ll get her back or he won’t, our young lover. Things will go back to normal or not, and that will become the new norm. It will be one or the other, and all that suspense hinges on a hard K. Our Man remembers when it was that simple, and the woman has both hands in her bag now and is looking down at the gray platform tiles and he can tell from here that she’s muttering aloud, and the bag is moving around like her hands are busy in hiding.

The band stops on a loud, jangling note and the musicians laugh together while discussing what they’ll play next. First Our Man feels a rumble, then he spots the nose of the next train approaching where the track curves coming into — or out of — the station. So he steps up to the yellow safety strip of nubbed rubber at the edge of the platform, lining up across from the stain on the concrete wall opposite that he knows from practice is exactly where one of the train doors will open if the driver hits his mark this morning.

The woman with the bag steps up, too, but far enough down the platform she’ll be in the next car where someone else can wonder what’s in her bag; Our Man will make a clean break, out of sight, out of mind.

But Our Man will remember her later, despite himself, when he gives in to temptation at his desk in his office and finds a clip of that Scorpions song on his computer. The video, the guitars, and the singer will all be as he remembered. But as they build to the chorus and toward that hard K he’ll be shocked. Confused. A bit lost. Our Man will find he’s remembered it wrong, that the G isn’t even a G, it’s not there, and the lyric is delivered as still lovin’ you with the softened N sliding into the Y like one letter, one word, like a whole border brought down.

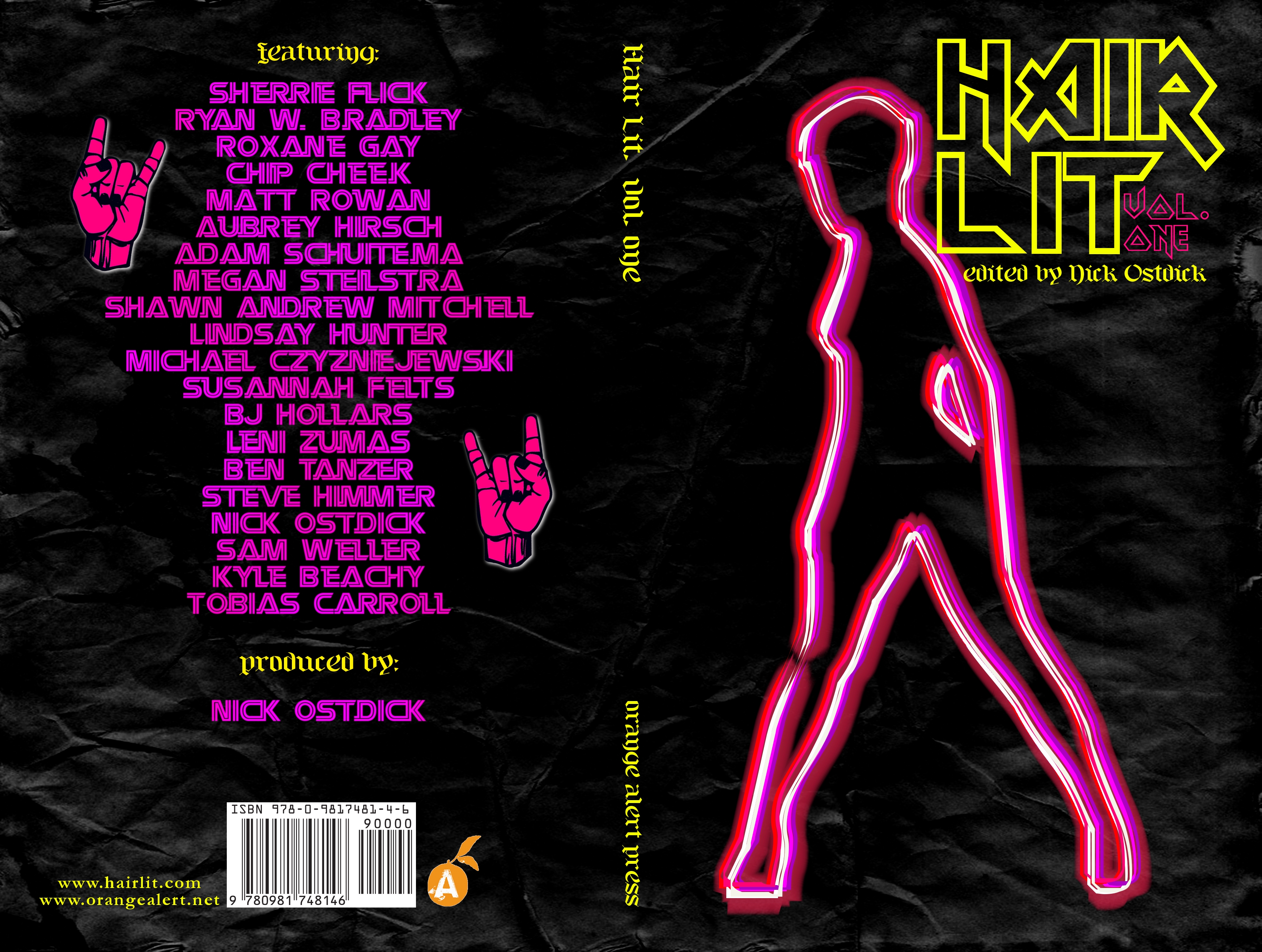

Hair Lit, Vol.1 is available now.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.