It’s three thirty in the morning and I’ve been up with Chris Koehler, my former professor, and the artist and co-creator of Legend, for the fifth night in a row, trying to match his capacity to function as a night crawler, as we drive towards the rapidly approaching deadline of our next issue. Legend is our debut comic book about dogs and cats attempting to rebuild a world humans destroyed. And let me tell you, after days with little sleep, the notion of apocalypse feels realer than not.

When I started getting a little more than curious about making comics, I did so from the point of view of a fledgling novelist, who wrote and published an avante-garde superhero novel, League of Somebodies, in 2013, to be followed by a hybrid horror novel, The Silent End, in 2015. I’d been comics’ obsessed since the early nineties, when publishers like Dark Horse and Image were charting out new constellations. For my generation, comics weren’t exactly as ubiquitous and diverse as they are now, but the tide was turning. I treated my comics with more care and attention than anything else I owned, buttressed by a passion for novels of all sorts. I moved gradually towards writing prose as I entered college, and years later in 2009, after spending years writing League of Somebodies, a novel about superheroes inspired by the likes of Michael Charon’s Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, but with added heaps of absurdity, I got it into mind that as opposed to writing fiction about comics, I should probably start making them myself.

While toying around with pitches I modeled off those of writer friends that cross back and forth between comics and novels, I came upon a nascent graduate program at California College of the Arts. Simply titled MFA Comics, I ended up submitting an application that consisted primarily of League of Somebodies, furnished with a couple low-grade pencil and charcoal drawings I begrudgingly eked out because they were required, and to my chagrin, was accepted. The low-residency program consists of 4 weeks of class during the summer. Classes are held for 10 hours per day, culminating in 200 hours of intense multi-focused tutelage in under a month, to be repeated for three summers in a row, and padded during the spring and fall with online courses. Nearing the start date was not unlike coasting towards a misty island atoll on a tiny, motorless boat. I came in curious, a little nervous, but confident overall, feeling like I would ease into the medium I’d romanticized for years. Because writing was writing, after all, and a story was a story. After years of practice, I thought I could, at the very least, handle that.

Three days hadn’t passed after the program started, however, when I began to feel like everything I’d learned about narrative had to be reevaluated, if not thrown out the window whilst screaming in terror. In a class full of visual artists, all of whom had gone to art school and had talent to burn, I was a clear outlier, with lackluster drawing skills and a steep learning curve ahead of me. I’d become so entrenched in my education as a novelist that words had became a liability. A stubborn tendency to overwrite I’d been trying to shake transformed from a wart to a festering sore as I came up against visual literacy, not understanding that the medium I’d been trained in was quite narrower in its scope that I’d realized.

In my early attempts to write comics, I found that I had a hard time building a sense of immediacy. Good novels require urgency, yes, but comics rely on visual media, and thus require even more. In order to better understand how I might approach comics’ writing, I was advised to read original scripts from different comic writers I admire, most of which are available online. I of course read scripts for Alan Moore’s Watchman and Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series, being that, especially in the case of the latter, each is familiar with traditional prose, and I love their work dearly. I also read everyone from Brian K. Vaughan to Brian Wood, from Mat Johnson to Noelle Stevenson, anyone whose work I found in engaging. I needed to understand how exactly words were used to carry the visual narratives I admired, particularly when it comes to addressing an artist.

As I read, I began to understand that comics’ writers could be as prescriptive as they liked when describing panel layouts, imagery, and scene, but only with the specific goal of addressing the art itself. Comics’ writers could describe the length, location, and angle of a panel, dictating the visual subtleties that would be found within by relying more on traditional scripting techniques, or they could be more open ended by providing a generalized overview, borrowing from the Marvel Method. But either way, prose became a private affair, as opposed to being on full display, as in novels. Dialogue and narration became a place for a writer’s prose style and character to shine through, but (with some notable exceptions, like Alan Moore, for instance, for whom writing is more of a direct feature) still leaned towards minimalism, in order to allow the image to carry the weight it requires. From reading scripts, I started to learn that, if a writer wasn’t careful, he/she could stymie an artist. This is something I still have remind myself of currently while writing Legend, as I run into situations where over-writing interrupts flow. While there are advantages to having a background in novel writing coming into comics, I’ve had to become comfortable with leaving a great deal of what I’ve learned behind.

Regardless of structure or intent, a novelist must paint a picture for a reader with words. And not just a picture, but a series of pictures, and characters who cross back and forth between those pictures, and an intricate matrix dictating how those pictures should be hung, with specific frames and heights for each. As rigorous as that is, pictures made with words engage the mind through voice and imagination, as opposed to the eye.

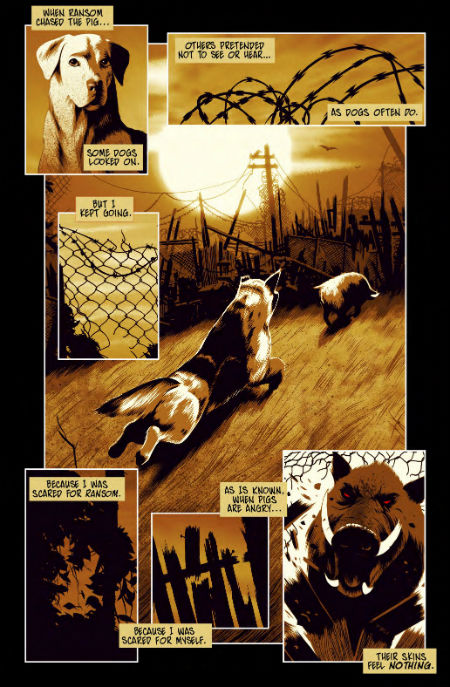

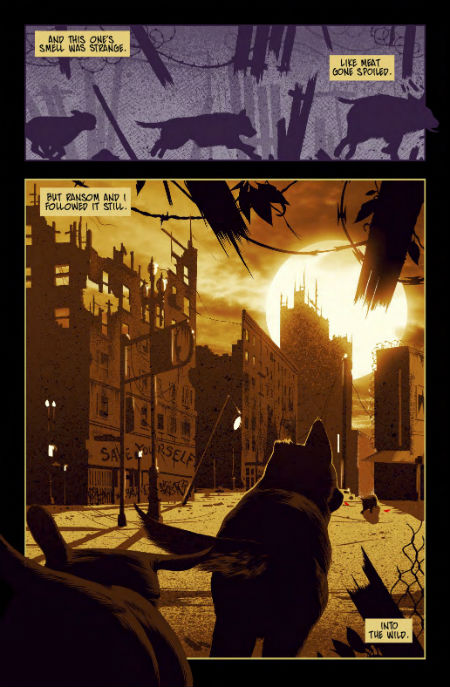

Though writing for an artist, especially one as exquisite as Chris, has become an amazing experience, it was alien to me when I first started out. I had to learn that whatever I write will be interpreted, and necessarily so. The idea of achieving a singular vision in collaborative comics is not just selfish, but impossible. Both parties have to feel confident in projecting their visions, and you have to surrender a bit of control. When I imagined the Endark, for instance, the principal threat in Legend, I provided a description of what it would look like. Chris nodded his approval as he read, and said that he knew exactly what he was going to draw. I was amazed by that fact alone. That an artist could visualize something so crisply from what I’d written. When I finally saw the Endark Chris had created, it wasn’t exactly what I had imagined. It was better. It had taken my vision and made it real. It provided perspective I could never have arrived at on my own, and transformed a raw idea into something that had to live and breath and occupy space on a page. Something, in a way, alive.

Though I also write educational comics for a company in Oakland, California, Legend is my first foray into a series that capitalizes on my own creative property. Chris and I set out to spin a tale of mystery, horror, and hope that would combine Chris’s moody, noir sensibilities with my own bizarre notions of intrigue. Our story of dogs, cats, and other animals attempting to face down dangers left behind by a presumed-perished humanity is one that opens up more and more as we go. And in that process, I am consistently surprised by how much I’ve grown as a storyteller. Both novels and comics have taught me a lot, but it’s in the space between the two where I feel happiest to reside, where, through travelling back and forth between worlds, every step is a lesson in what a book can truly be.

Sam Sattin is a novelist, comics creator, and essayist. He is the author of the THE SILENT END and LEAGUE OF SOMEBODIES, described by Pop Matters as “One of the most important novels of 2013.” His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Salon Magazine, io9,Kotaku, The Fiction Advocate, Publishing Perspectives, The Weeklings, The Rumpus, The Good Men Project, Litreactor, Buffalo Almanack, SF Signal, and elsewhere. Also an illustrator, he holds an MFA in Comics from California College of the Arts and has a creative writing MFA from Mills College. He’s the recipient of NYS and SLS Fellowships, and lives in Oakland, California.

Images from issue 1 of Legend by Samuel Sattin and Chris Koehler / Z2 Comics

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.