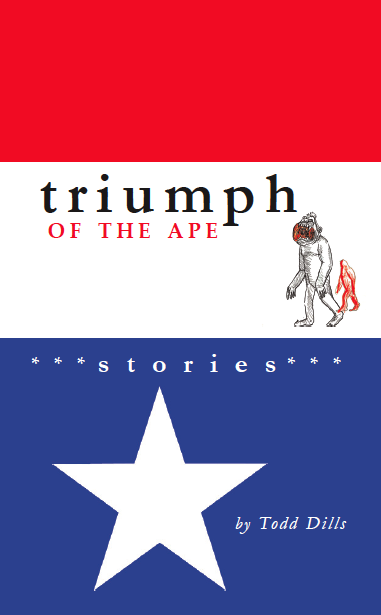

Triumph of the Ape, the new collection from THE2NDHAND editor Todd Dills, abounds with loving descriptions of Chicago and the Southeast, deadpan humor, and occasional shifts into the surreal. Last week, we noted that it was “a fusion of Barry Hannah and Touch & Go Records” — both aesthetics that we wholeheartedly support. We’re happy to have an excerpt up from it today.

DEATH IN HAMMOND

My buddy Mort got married on April Fool’s Day, 2005, his reasoning at upwards of 40 years old somewhere between a practical wager and blissful capitulation — both on or to the woman, if you ask me, though I’m not too young to be aware of the two-way street of these things.

Before all that, there was a bachelor party, of course, and even before that I had him over in lieu of a formal celebration for our yearly get-drunk over the Daytona 500 to start the year out right.

My relationship to NASCAR is a mite complicated, as is any Southern expat’s, but it essentially fits the following parameters:

1) I don’t typically much care for its fans, unless they’re related to me — Mort’s an exception.

2) I was raised on a steady diet of Richard Petty and Dale Earnhardt, but when Earnhardt died I was a long way from Calvary Baptist in Charlotte, N.C., and I was mostly amused by the news of the regional, may have even been national, TV coverage his service received (delivered via a fitful, sobbing telephone call from my redneck brother).

3) Chili goes well with it.

4) Beer too.

Mid-February and the first race of the season, the grand Daytona 500, came on quick this year, but I met it in plenty of time to muster my few friends for the end-of-Speed Week hangout at my place: plenty of chili, plenty of beer, and in addition to Mort there was Erk, a nonfan, as it goes, but a man with a large beard who shared a name with the famed Georgia Southern football coach (formerly of the UGA junkyard dawgs defense) Erk Russell. Erk’s likewise a man with a mind open to pretty much anything, really, and particularly the idea that a latent homosexuality pervades much of men’s professional sports and its enthusiasts, an idea very hard to discount at any moment — Erk makes a hell of an argument.

And Henry David Cocteau, whom we call HD, also a nonfan but from North Carolina, which makes us brothers, of a sort, in Chicago. HD’s attraction to NASCAR is all regional nostalgia, boyhood memories of sitting with Pop by the wood fireplace talking Earnhardt bump-steer and old Richard Petty lore.

And Mort, of course, a new-NASCAR enthusiast if I’ve ever seen one — he wears an earring with his DeWalt cap and diminutive wrap-around shades. His enthusiasm for Matt Kenseth seems to spring from an apparently loyalty to DeWalt tools, not that he ever uses them, really; he does live in Chicago, city of big service, and works in a bar far (metaphysically, if not geographically) from any real garage.

We were primed. Or at least I was. My brother, however, was ecstatic. He lives for this shit. Good ol’ boy Dale Jarrett, among the old guard of drivers in our time, had won the shootout pole position-determining race the previous week and thus my brother put all the money he could afford on the man in one of those offshore online-gambling ops. He’d been calling me daily over the preceding week with news from South Carolina, from the heart of the near-psychotic fandom that resides somewhere in his left brain. He “couldn’t fucking wait” for the green flag, when Jarrett would by any means necessary whip every other driver out there. Yes, to hear the boy talk you’d have thought he was a shoe-in for victory.

When race time arrived, chili beginning its fourth and final hour of simmering, beer on the back porch cooling naturally in the Chicago winter, after a viewing of the unfortunate singing of none other than former beauty queen and Playboy pinup Vanessa Williams and countless country-music losers, me and Mort — HD and Erk hadn’t yet arrived — watched Jarrett promptly lose 20 spots due to a quickly failing tire. My brother called and was cursing, over the phone. Mort invoked the great Dale Earnhardt when I passed him the handheld, my brother in mid-curse, as he said, “That’s racin’.”

I listened to the attendant yowling, Mort painfully pulling the receiver away from his ear, with equal parts glee and empathetic consternation, for the NASCAR fan is like his favorite driver and competitive to a fault, though likewise always mindful of the ever-present possibility of death. My brother and I are inveterate hypochondriacs. In fact, I was on the front end of one of my months-long attacks for the 500 this year, and as Mort put the phone on the floor, where my cat had proceeded to sniff at it, then screeching a little at my brother’s voice blasting forth, I turned my head again to the television just in time for a spectacular wreck involving three of the tour’s no-names, sending a spike of pain through my lower left ribcage, whereupon my mind seized on the pain and my heart beat loudly in my chest. I lit a cigarette. “Damn,” Mort said, pointing stupidly to TV, then to the phone on the floor, from which my brother’s voice now could be heard saying “Hey! You there? Was that a damn cat?” He hung up, eventually, and wouldn’t call back again, not even when Jarrett was charging through the field toward the front at the end of the race, when it looked like Jarrett might actually contend for this one. It was a shame, too, cause had he called to gloat it would’ve blown up square in his face just like Jarrett’s chances for victory: I try never lose an opportunity to get one up on my brother, and in being a racing fan it was too easy. The highly partisan fan suffers with his driver. I was relatively nonpartisan, if occasionally I pulled (along with the rest of my small crew here except for Erk, who couldn’t give a shit either way) for Mark Martin, at the time another old-guard veteran we couldn’t help but be partial to on account of the grand tragedy of his corporate sponsor, the erectile dysfunction drug Viagra. It’s not something we’ll even much talk about, you know, until Martin creeps into the top five, maybe, or say it’s getting late in the race and the little ticker across the top of your TV might be telling you, lap by lap, that the old man’s creeping up toward the front and then, with maybe 50 laps left in whatever race, you might feel compelled to put all shame aside and raise a toast to the victims of erectile dysfunction the world over, to raise one for the blue No. 6 Viagra Ford of Mark Martin, native of Batesville, Ark.

Yes, the old boy Dale Jarrett finished 15th after creeping into the top ten and I imagined my brother was none too pleased (goodbye, $500). But Martin, well, let’s just say that me and HD and Mort spent the last 20 laps of that year’s Speed Week silent as elves, our eyes and minds locked on the events at hand. Martin was shifted back and forth between second and third and fourth places in the final laps, before a wreck back in the field and ensuing caution period, after which the youthful power trio of Dale Earnhardt Jr., Jeff Gordon, and defending season champion Kurt Busch fought it out to a Gordon victory. The driver of the Viagra car finished sixth in what was purported at the time to be his last-ever Daytona 500 (he reneged on his retirement plans later in the year, though), but it wasn’t such a bad showing. Me and Mort and HD were all down, a little, though the drinks probably had something to do with it.

Erk, though, was beaming, always a joke at arm’s length, if not in hand. “Martin blew his load, didn’t he? Or maybe he just couldn’t get it up,” Erk said. We scowled, went out back for the cold that clears the air, for a cigarette, another beer. Take the day onward, we figured in our sudden dysfunctional camaraderie. Young and defeated all. On to the Rainbo bar, where we knew some people, even if we had to take the traitor namesake of the great Georgia football coach. Erk came out onto my porch as we all shivered and lit up our second cigarettes and invited himself along, but it didn’t much matter. At the bar, Erk even joined in on a toast to Martin’s failure, likewise our own. My shoulder burned, now. I cracked the tension out, poured the shot down my throat and thought, if we ever grew up and got married and started careers and all that, God help us. Mort was on his way, anyway, and I wouldn’t remember much after the toast, wouldn’t see any of them again before Mort’s bachelor party two months later.

The celebration — or collective lament, as bachelor parties go — began at a Chicago Franklin Street steak house known for its asinine attitude toward the plebeians who frequented its halls hoping to brush elbows with the nation’s elite. Consequently, the prices were jacked to beyond even reasonable extremes, said elites enjoyed the comfort of the first-floor bar and cushioned booths, and the rest of us, well, we were relegated to a cavernous dining hall upstairs where the volume of conversation from neighboring tables forbade even the possibility of communication rendered in anything under a shout. Thankfully, I had to work through most of this first portion, so I missed out on contributing my $100-plus to the final tab when I got there, Mort and company shortly on their ways to the door and each of the men in his own way — some surreptitiously eyeing, some outright ogling, one to the point of even snapping a few pictures — with his gaze stuck to the dignitary across the room, Mr. Keanu Reeves, aka Neo, aka Ted in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, by far his best flick. The picture taker, a character I knew only as the organizer of the evening’s festivities, a man close to my age, younger than most in this party of near middle-agers — Mort was 15 years my senior — was collared by the bartender and reprimanded very haughtily. I laughed a little too loudly for the situation’s gravity, and the organizer blushed mightily. I chanced a long glance Neo’s way on our forced way out the door. Keanu Reeves had to be nearing 40 himself, I figured, though he looked the very picture of 28, my own age. I clutched my chest; the possibility of death, on a night like this, was ever near.

And soon enough we were afloat in Jack Binion’s Horsehoe Casino — in Lake Michigan just off the coast of industrial Hammond in northwest Indiana. On each floor of the giant boat, way off in a corner but close enough to the floor-to-floor stairwells to be quite conspicuous to the more than casual observer, placards hung on the walls with directives as to the appropriate course of action in the event of the boat’s capsizing. At first I thought they had to be a sardonic joke on the part of the owners. Clearly the quadruple-decker casino was in no conventional sense a boat. We were not sailing or, I suspected, even floating. Mort filled me in, though, on the machinations of the last decade or so of Midwest casino law, in particular that of Illinois and Indiana, the latter of whom beat the former to the punch by allowing casinos to open at all, in the early 1990s, following a decision by the state of Iowa, in turn, in the late ’80s to allow gambling during sailing excursions, the rationale being that if casinos were relegated to the state’s waterways, any attendant social disruption in the surrounding communities would be avoided.

The Iowa and subsequent Indiana casino-gaming industries, as Mort called them, believe it or not, hoping as they did to encourage tourism, thus struggled from the beginning — the inconvenience of waiting to sail and then return produced a dearth of idle tourist-gamblers, encouraging only the professionals, who were wily and prone to winning, of course. The take of operator, the state, was incorrigibly low.

Then Illinois, sandwiched between the two states and within striking distance of residents of each, introduced its own version of riverboat gambling but quickly went dockside, on example of the Mississippi model, allowing for permanent air-conditioned gangways, free 24-hour access to and from gaming parlors, and popular participation, generally, the drawing in of suckers from all over the region and beyond. This killed Indiana’s enterprise, until they followed with exactly the same thing. Hence the relative absurdity of life-preserver directions, one had to think.

Or maybe not.

Mort couldn’t relieve my mind of the logistical, physical question that remained about the boat’s “docked” status — were we floating on water, or were we somehow moored by a solid superstructure under the boat’s base, immune to any possible rising or lowering water level and from the rocking attendant to the arrival of any tsunami- or otherwise smaller-size wave?

“It’s a boat, man,” Mort said. “Boats float.”

Mort is a lover of life — temperless, loud and boisterous. I wish he and the wife well. As for me, I wasn’t convinced; death was on the mind. Still coming out of the bout of hypochondria that began more than a month before, I remained half-convinced I had lung and throat cancers (as I continued to chain-smoke), diabetes, and astronomically high blood pressure at once and that my heart would give out at any moment. I was walking around, smoking, drinking, breathing. It’s a weakness of mine: the existentence of death, the very fact that it ever happened, was enough to lead me to this kind of thinking.

Plus, after every beer consumed, on the walk to the bar in the high-stakes parlor on the third level, my chest pounded harder at every imagined keen of the floor, the absolutely level whiskey glass atop Mort’s chosen slot machine be damned. The ship was sinking, I convinced myself. “Do you feel that?” I said after my fifth trip to the bar. Mort, self-described “slot junkie,” was engaged now with a contraption that had a winning hit matrix extended beyond just a single line across the slot screens to include a myriad other possible combinations along a grid that took up a majority of the display.

“Feel what?” Mort said. He hit the maximum bet button, in this case equal to a ten-dollar wager, and the wheels rolled, stopping with a series of BARs spread diagonally across the display grid. The machine bleeped happily but put Mort up only two dollars. The improved odds on this particular style of machine seemed to feed or enhance the addictive properties of the compulsive behavior. Mort lost a hundred dollars on this one alone, but it took him damn near two hours to do it. The apotheosis of the law of diminishing returns, the slots will hit on a maximum bet occasionally, and you’ll still be down two bucks, depending on the corners of the grid you match. Only rarely do you score a direct hit. Then, it’ll let you win a buck or two back, then go down only four after betting ten. It’s a bullshit game, and this I told Mort.

“I’ve won big before,” he grinned up at me. Of course. This is the problem. As in life and death, anything’s possible, you tell yourself, and maybe even rightly so. You know your own history, anyway, that time you went up $200 on a single-line slot and cashed out, called it a night.

Mort went up overall tonight after a big hit on another machine, and I was like, “You oughtta give it up right there, man.” But Mort only grinned, sarcastically, under his handlebar mustache. He took his ticket on to the next machine. “If I quit now, I’m only up fifteen bucks for the night,” he said. “Shit, I’ve done better than that.”

Anything’s possible. HD, who like me was here only on behalf of Mort and consequently only interested in the drinks at the bar, got married at one of the lored drive-through chapels in Las Vegas. An auto aficionado, you might call him, he and his gal went on a long road trip in the ’61 Chrysler he’d kept up since the mid-’80s in Florida, in the ’90s hauling it to Chicago, where it now spends the winters in a garage and still gets along quite well, or so HD says. The romantic all-possibilities sense behind the trip took its toll, as he explains it — plus they’d bandied the idea of a Las Vegas wedding about in the weeks preceding the excursion — so with the juggernaut they rode approaching the desert casino city and the ease of obtaining a marriage license ($55 and a valid ID, he said) high in their minds, they jumped.

Las Vegas is of course the envy of all locales that would bolster the city government’s coffers by offering big-box casino gaming; their cheap marriage licenses are part of the tourist economy, too, as are requirement written into the local code that hotels with a certain high number of rooms come with a particular square footage of casino space. Indiana’s nowhere near there; looking around I could recognize more than a few faces from the city and a number of men and women who, to my stereotyping gaze, had that hangdog tired look one gets from working at a steel mill all day (Gary Works, not to mention a number of other large factories, was 15 minutes down the road), and in general the air is full of local desperation. Indiana doesn’t require the existence of large hotels along with their riverboats, as does for instance Mississippi, where Biloxi and Tunica county south of Memphis had long since become destinations to rival Atlantic City. And Hammond, along with much of the industrial northern Indiana shores, with the collapse of the American industrial economy complete, was a veritable bastion of macroeconomic decay. It seemed obvious to me that the casino could only serve the purpose of completing the death, sucking the region’s desperate denizens dry. Naturally, though I lived among the bright lights of the ivory tower to the north, this includes me.

The more disgustingly drunk I got, the less hope I had.

By the end, I would pull a hundred from my bank account and wade through the slots, emulating Mort’s method of picking the lucky machine, whereby he waves his right arm in front of each until one makes a sound he deems worthy of a winner. My technique was decidedly less lucky, or less developed, if you prefer, as it took me a mere 20 minutes to wipe out my hundred. I found HD by a blackjack table with the remainder of our party, sans the bachelor still wading through slots on the floor above us. Here, essentially below-decks, minus the continual bleeping of the slots, one could listen carefully and almost hear the telltale creak of the floating or sinking casino, or one could well imagine it, as did I as HD watched the folks at the blackjack table engaged in a to-the-death round. It was quickly becoming clear that the party’s organizer was something of a gambling junky. He was losing big-time but was all wide-eyed glee. The only female with us — a lesbian who in a bit of fence-hopping HD at least couldn’t approve of (in fact, he was vocal about his disapproval, shaking a fist into the air and bemoaning the fact that she) would be attending the bachelorette party as well (“Boundaries!” boomed HD, “boundaries, dude. They exist for reasons.” I tipped back my last beer and laughed heartily.) — was pulling in gobs of cash. And as we stood there, waiting, Mort walked up alone and shot his thumb to the door, he wanted to make last call at his favorite bar back in the city. But these folks were high on the lesbian’s winnings, or on the organizer’s losses, or both. I smoked a cigarette and closed my eyes. “This motherfucker’s floating,” I said, as I imagined I could feel the ground swaying, buoying me up, the dropping me down, with it. “I can feel it,” I said. I let my head roll way back.

Before I passed out, it was Mort’s voice in ear, cutting through the clamor of voices at the blackjack table. “It ain’t Fool’s Day yet,” Mort said. “Shut the fuck up.”

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.