Sitting in front of me are a pair of books with punk rock and the Lower East Side at their core. One, Rayya Elias’s Harley Loco, is a memoir; the other, Sascha Altman DuBrul’s Maps to the Other Side, feels more like an anthology, a document of writings made by DuBrul over the course of a decade in his life. Neither is easy reading: Elias writes frankly about her addiction, the deaths of loved ones, and a series of bad relationships; DuBrul also writes of death, of psychological torment, of life’s shocking tendency to unravel when you least expect it.

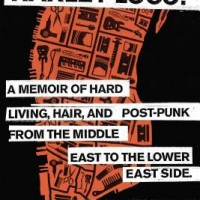

Rayya Elias’s memoir Harley Loco covers a vast geographical, cultural, and emotional space. It opens with her early childhood in Syria; soon afterwards, her family moves to Michigan in the late 1960s. As Elias came of age, she discovered punk rock, a skill at cutting hair, and a penchant for controlled substances. Beginning in Detroit she made music, and her accounts of performing live make for some of the most compelling moments of the book. (For those who are curious, there’s a recording of her band that’s been posted on Elias’s website, along with her more recent work.) Like much of Tony O’Neill‘s work, her accounts of addiction (and of cleaning up, and of relapsing) are visceral and chilling to read, evoking both the attraction of a certain drug-fueled lifestyle and starkly narrating its inevitable collapse.

Elias includes a lot here: accounts of her family (including a memorable conversation about sexuality with her terminally ill mother); a portrait of late-80s and early-90s New York City; discussions of Syria in the mid-1960s; and odes to the art and technique of cutting and styling hair well. Elias’s work with hair ends up providing the book with a kind of through-line: it’s a skill that allows her to move to New York, and it provides a useful craft to have in a variety of unexpected places. And, for a book that abounds with grim scenes of addiction, squalor, and death, it serves as an unexpected way to summon a hard-earned beauty.

As I read Maps to the Other Side, I realized that I’d encountered its author’s work before. Back in my zine-editor days, I’d been sent a copy of DuBrul’s Carnival of Chaos, and his name stuck with me. Maps to the Other Side is a collection of shorter work that appeared in zines and anthologies, often prefaced by DuBrul’s accounts of how they came to be written. Like Elias, DuBrul’s life has been far more eventful than most: he’s been a musician (in Choking Victim), has a prodigious knowledge of seeds, and started a nonprofit to deal with mental health issues. At the same time, he was also struggling with his own internal conflicts; the book’s subtitle, The Adventures of a Bipolar Cartographer, suggests the nature of these struggles.

In the book’s final pages, when he writes of encountering a former bandmate, DuBrul writes with perhaps his most open tone about his life. A common theme in Maps to the Other Side is DuBrul’s fondness for self-mythologizing: superheroes and science fictional concepts frequently crop up as metaphors. Maps to the Other Side is dense with information, whether on the history of seed libraries, the process of converting a car to run on biodiesel, or the complex evolution of Chumbawamba’s cultural provocations. Reading DuBrul’s book was often informative and sometimes frustrating, the contrast between the more grounded DuBrul who narrates this and the more frenetic voice of his younger years making itself felt. His book is also, however, a sharply written evocation of particular places, some gone: the Lower East Side in the 1990s, the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle; an organic farm in upstate New York; the zine Slug & Lettuce. And it feels like a necessary document of a place where several vital scenes overlapped — even as DuBrul also chronicles the contradictions that overlap unearthed.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.