This year I’m being careful to call this post “The best books I read” as opposed to simply “the best books” because, as in any year, I didn’t read every major title that came out. I can’t say that the few titles on my list are the best books that came out this year, because there are so many that I didn’t read. And in fact many of those that I skipped were the most hyped, award-winning, ballyhooed books that came out. At this point in my life as a reader I know what interests me and what doesn’t, and frankly, there are some novels that, no matter how much wild praise they garner, turn me off as soon as I hear the plot synopsis. For example, the Wolf Hall series (I know, I know, I’m sure if I just gave them a chance I’d be hooked). Or The Round House or Yellow Birds, both of which were National Book Award finalists this year.

I stuck to what I like and I’m glad of it, because my free reading is what fuels my subway rides, and this was a great year of subway rides. I moved to Brooklyn in August, which has made my trip to work go from eight minutes (seriously, that’s what it was for two years) to just under forty-five. I use the extra time to whip through novels, and thanks to the longer journey, I now read about 100 pages per weekday (I don’t intentionally “speed read” but I’m quite fast when interested), which means I get through just over one novel a week. Story collections, for whatever reason, I approach differently: if I’m reading a book of stories, I typically have a novel going at the same time, and I take breaks between stories to read the novel.

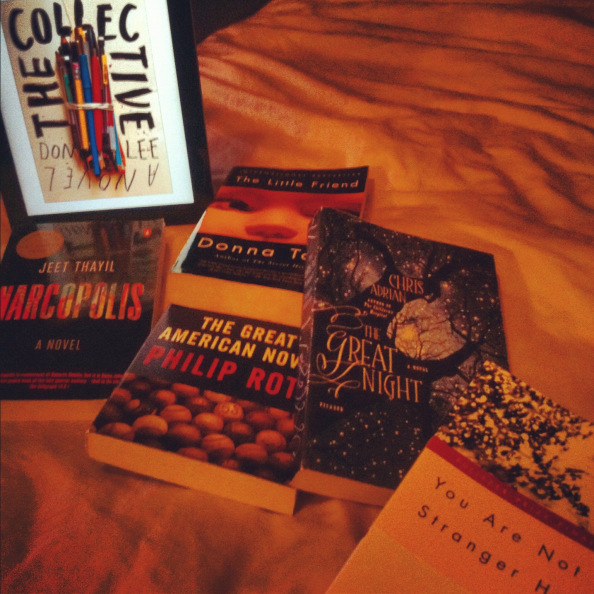

Anyway, in no order (apart from saving my very favorite for last), here are the very best books I read in 2012, many of which were new this year, but some of which were not.

Winners

The Great Night, Chris Adrian

In last year’s post, I raved about The Children’s Hospital. That remains perhaps one of the best novels I’ve read, period, or at least one of the most surprising. I had the pleasure of seeing Chris Adrian talk this year at the New Yorker Festival, in a panel on faith with Nathan Englander and Marilynne Robinson, and his brilliant wit on the page is as apparent in person. Adrian has been a writer, a doctor, and soon a pastor, and his writing shows all of this. The Great Night is far more than a modern version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream—it is about loss, as all of Adrian’s work is (his younger brother drowned as a child), and about sex and food and bodies and fear. It charts three different relationships that collapsed. It is dark, and scary, and a lot of fun. Here is Adrian’s version of Puck, who in Shakespeare was merely a mischievous sprite, but here is basically the fucking Devil: “People and faeries, animals and spirits—any observing entity—each saw Puck a little differently. What you saw depended on how you were feeling: he was often the image of one’s worst fear or most troubling anxiety. To some of the faeries he looked like a naked boy with a luxurious Afro… But some saw him as a sliver of flame, or a blackness heavier and darker than the black air, or a fluttering pair of dark wings.” You don’t need to have read the Shakespeare play to enjoy this novel, though it certainly makes his genius more obvious. Adrian knows about love, and beautifully charts, in all of his writing, the way it begins and the ways it can wither: “A person could seem magical and intriguing, like the answers to your prayers and your problems, and then later, twenty minutes or two weeks or three months or a year, have become, while you looked away for a moment, something or someone else entirely.”

The Pregnant Widow, Martin Amis

I read this in the summer, which was the perfect time to enjoy a novel that is so purely Amis doing Amis: young aspiring writer spends a summer in a castle in Italy, living with two girls, one of whom he’s dating, the other one he lusts after. It’s balls-out fun. But it’s also beautifully written. I had been turned off by the last Amis novel I read, Dead Babies, which was basically disgusting and pointless and upsetting. But The Pregnant Widow perfectly captures the feeling of being an ambitious, impatient, horny, intellectual boy in your twenties. He seems to remember it all like it was yesterday. The novel has its down moments—I didn’t much care for interjections into Keith’s life as a twice-divorced adult, nor for frequent snippets from the Echo and Narcissus myth—but for the most part the scenes between Keith and the women he desires are pitch-perfect. When Keith, who has been waiting and planning for the entire book to somehow hook up with tall, leggy beauty Scheherezade, ends up surprising us and himself by instead hooking up with the much ridiculed visitor Gloria Beautyman, the way it happens, especially the dialogue, is so well paced and fun it’s like a dessert. He walks in on her in the bathroom, praying, naked, when she’s supposed to be home sick from a day trip. “I always pray naked,” she says, and then: “Do you have any objection?” A voice in Keith’s head tells him, “There’s no need to hurry. Everything is as it should be… Never worry. Proceed. It has all been decided.” He takes it slowly, lets her lead him into it. His towel falls, they stand in front of the mirror together, and she coos, “Oh, I love me. I love me so.” She touches herself as he watches, dizzy, and she says things like, “Look what happens when I use two fingers.” It’s paced just right, and it’s sexy and feels real. I don’t want to suggest, by the way, that the novel is merely a fun romp about a summer in Italy. In a larger sense, it’s about the sexual revolution, and about gender identity. Gloria, in fact, wonderfully represents female empowerment (Keith tells her, “You are a cock,” and she responds, “How onearth did you know? I am a cock. And we’re very rare—girls who are cocks.”) If you’ve never read Amis, this would be as good a place to start as any. Then read Money.

Battleborn, Claire Vaye Watkins

Another story collection that blew me away. Watkins’s short stories are muscular and unflinching. They almost all take place in Nevada, and the language is fittingly unsentimental, and dusty, and hot, if that makes sense. Of course the most notable story in the collection is the first, “Ghosts, Cowboys,” which flirts with the real-life fact that Watkins’s father was an associate of Charles Manson. But the story is more than that, and guides us nicely into the rest of the book, setting the tone, alerting us that these stories will be, if not necessarily sad, certainly raw and matter-of-fact and often upsetting. In “Rondine Al Nido” two high school girls head to Las Vegas and pick up two older guys, go back to a hotel room with them, and have sex. The more aggressive of the two girls, the leader, does it all as a sort of self-inflicted punishment for God knows what; the other isn’t happy, but is trapped by the situation. We learn that later, “By September, she and Lena will not even nod in the halls. When the announcement comes over the intercom first period, our girl will try to make herself feel the things she is supposed to feel: grief for dead people in buildings she did not know existed.” The outer framework is that the surviving girl is now telling this story to her current boyfriend, who is disturbed but attentive. “The Past Perfect, the Past Continuous, the Simple Past” is about a foreign tourist who loses his friend in the mountains while hiking, and spends the next few days, as the police search in vain, at a brothel farm. In “Wish You Were Here,” a group of childhood friends, now in their thirties or so, reunites and goes camping. This bit of dialogue absolutely floored me, when the female protagonist, married and pregnant, hits on one of the friends (“hooks her fingers in the waist of his shorts”) after everyone else has gone to bed: “He steps back, allowing her hands to fall from his waistband, shaking his head… My God, he says, kindly. What a nightmare you must be.” I can’t recommend these stories enough and I’m sure Watkins will continue to impress.

The Art of Fielding, Chad Harbach (second read)

I gave The Art of Fielding another read after I lent it to my dad, who never reads fiction, and watched him enjoying it, devouring it. I couldn’t resist. When I reviewed this book a year ago for The Rumpus, I pointed out that what was billed as a baseball novel is really a college novel about life on campus. That’s true, but on my second read I picked up on a sub-theme to which Harbach turns time and time again, an important one that fascinated me and that I missed the first time: the idea of routine, of falling into a strict schedule, and the appeal (for Henry Skrimshander and Guert Affenlight) and fear (for Pella Affenlight and Mike Schwartz, I’d argue) of that cyclical lifestyle. Early on, when he’s training with Schwartz, we see Henry, the rising star shortstop, discovering routine and relishing it: “Every day that summer had the same framework, the alarm at the same time, meals and workouts and shifts and SuperBoost at the same times, over and over, and it was that sameness, that repetition, that gave life meaning. He savored the tiny variations, the incremental improvements—tuna fish on his salad instead of turkey; two extra reps on the bench press.” Much later on, when Henry’s on-field performance has collapsed and he’s quit the team and spends each day lying around in Pella’s apartment, peeing into Gatorade bottles like Howard Hughes, he wallows in self-pity and longs for that routine: “All he’d ever wanted was for nothing to ever change. Or for things to change only in the right ways, improving little by little, day by day, forever. It sounded crazy when you said it like that, but that was what baseball had promised him, what Westish College had promised him, what Schwartzy had promised him. The dream of every day the same. Every day was like the day before but a little better. You ran the stadium a little faster. You bench-pressed a little more. You hit the ball a little harder in the cage; you watched the tape with Schwartzy afterward and gained a little insight into your swing. Your swing grew a little simpler. Everything grew simpler, little by little… You improved little by little till the day it all became perfect and stayed that way, forever.” Harbach is cribbing a little bit from the earlier section, which sure sounds similar, and he’s also riffing on the end of Gatsby (“tomorrow tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther…” you half expect Henry to wish that “one fine morning” he can “beat on, boats against the current…”) But the point is well taken: it’s a pipe dream, a fantasy. Henry justifies the entire thing as “all he wanted,” as though it isn’t so much to ask, but it is. And he sounds like a brat. And yet what a perfect, moving, obvious theme for a book about college, that paradise where you enjoy the luxury of a routine that couldn’t be less like the one you’ll adjust to in the real world. You go to classes, study, write a bit, eat meals in the dining hall with your friends, go out on the weekend and drink and get laid. Then the next week you do it all over again. You get fooled into thinking it’s the norm, but it won’t last longer than college, which goes real fast, and then you adjust to a new routine, and you learn to understand that the lifestyle you enjoyed as a young person can’t stay around forever, nor can the people: some will lose touch with you, move on, some will even die. Guert Affenlight, too, when his illicit sexual relationship with male student Owen hits its stride, makes the same delighted discovery as Henry did from his workouts: “The routine became entrenched: After they did whatever they did that day, Owen would go out into the hallway and return eight minutes later, always bearing the same two steaming mugs… They sipped their coffee and smoked a cigarette, chatted, read Chekhov together… Such consistency suggested, or seemed to suggest,that Owen found their afternoons worth repeating, even down to the smallest detail. this was the dreamy, paradisiacal side of domestic ritual: when all the days were possessed of the same minutiae precisely because you wanted them to be.” Pella, Affenlight’s plucky daughter, isn’t so sure that rigid conformity to a routine is a good thing. Pondering the way that everyone on campus has been freaking out over Henry’s failure on the baseball field, she reflects, “It was amazing the way people hemmed each other in, forced each other to act in such narrowly determined ways, as if the world would end if Henry didn’t straighten himself out right now, as if a little struggle with self-doubt might not make him a better person in the long run, as if there were any reason why he shouldn’t take a break from baseball… but no, God no, he had to work hard and stay focused and grind it out and keep his chin up and relax and think positive and keep plugging away.” Pella herself has already had her “little struggle with self-doubt” from being in an ill-advised marriage, and she got out, fled to Westish College and now seems all the better for it. Schwartz seems to feel the same claustrophobia at the prospect of doing the same thing for years to come. When Duane Jenkins, the athletic director, offers him a gig that we would expect to be Schwartz’s dream job, he says no at first, because he “didn’t want to wake up in twenty years and see behind him a string of lives he’d changed, stretching out endlessly, rah rah go team, while he himself stayed exactly the same. Stagnant. Ungreat. Still wearing sweatpants to work.” The Art of Fieldingprobably has a number of other cherished tropes that I’ve still missed, but this one seems both obvious and insightful, a notion that follows us throughout college but which we don’t like to think about. Harbach’s novel, clearly, deserves revisiting.

A Million Heavens, John Brandon

John Brandon doesn’t get enough recognition. Maybe that comes from being a McSweeney’s author or from the slight, perhaps unexciting (at first glance) subject matters of his novels. But he’s quietly talented.Citrus County, about a boy in Florida who kidnaps the kid sister of a girl he likes and hides her in the woods, got a lot of buzz. But his newest is even better. The disparate characters (which include a wolf!) get distinct voices and motivations, and they don’t all necessarily come together in the obvious, trite way you’d expect from novels that have multiple perspectives. If you can get down with the flighty premise—that a boy in the hospital, around whom the entire town is rallying and sitting vigil, fell into the coma from having played a certain few notes on the piano—then the rest of the book is like magic.

Read all of Dan’s other favorites at his website.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + and our Tumblr.