Girl Friends

by Lynn Steger Strong

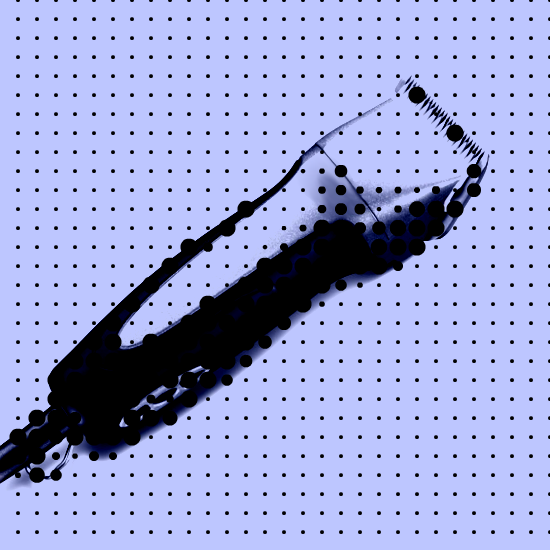

We shaved my head out on the roof, not even noticing the hair would fall down to the porch until it did. She noticed; she looked proud later when my roommates got angry. They didn’t like her. We’d made her, she and I, without their knowing, an extra set of keys.

It was summer and the buzz of her hands on the bare skin of my neck as chunks of my hair fell two stories down was the closest that I’d come to joy in years.

She didn’t tell me what I’d look like when it was over. At the time, I didn’t think I cared. I had images of waif-like women with large features staring steady back at me from pictures, pictures I’d found when we first discussed her shaving my head. I must have cared if I searched this. I must have been invested in how it’d turn out in the end. These women were all bare-faced as well as bare-headed: Sinead O’Conner, cancer victims, Yael Stone. All of them wide-eyed toward the camera. All of them gaunt and their features threatening from their faces, big and unprotected; it was the viewer though that seemed to need protecting then.

That my features were too small and my face already flat and blunt was not something I considered. That I’d gained weight and what was, would always be, too soft, had gotten softer, was something I was trying not to think about even before. My face, it turned out, the world, from me, needed protecting. But then, the hair had all fallen to the front porch of the house and we were sweeping it into the trash bin, and there was nothing to do but wear skullcaps or nothing at all and try to forget how it was possible I was making passers-by afraid.

Sometimes, in the days and months that followed, I thought I might be beautiful and just not know it. When she ran her fingers over the nubs of me, I almost believed. She said my face was perfectly symmetrical, my eyes an interesting—she said striking—green.

But then we’d go out and no one would look at me. When people did look, they were quick to look away. There were the thoughts, maybe, I have them now when I see women like this, that maybe I’d been contaminated in order to end up this way. Cancer, maybe, illness. Maybe I’d gone mad.

Men sought her out. I was a necessary obstacle they had to overcome. They would court me in their ways. Pretend to care about what I was reading when they approached us. We would bring books to bars, which I would read and she would hold close to her, flirting with the bartender or pretending not to notice the looks she got. I would nod and sometimes let myself pretend these men were actually interested in the things I said. When they had circled their chairs in the right way in order that they were facing only her, I just went back to my book.

She came home with me almost always these nights. When we made fun of these men later, it somehow felt like the experience of their desperate want was shared. It was mine insofar as I had gotten what they wanted. One of them called me a dyke bitch one night under his breath when I asked her, at 2 AM, if we could go. This one was attractive. Smart. I’d read an entire novel in the time we’d been there. Probably, she would have slept with him if I’d not made my face so sad when I’d asked if we could leave. If she’d not also heard what he’d muttered under his breath.

I was wearing a pink cotton strapless dress I’d had since high school, that had only seemed to fit in the dark apartment when I wasn’t looking in the full-length mirror. When she’d looked at me. I’d mistaken the forgiveness of its stretch when seen in less harsh lights, and now, having walked through the restaurant and passed a full wall of mirrors, having glimpsed myself from angles I would have never glimpsed myself from had I had the choice, I was now stifling hard the impulse to pull the table cloth off of the table and wrap it around myself. She wore a low cut black silk tank top and perfect pants. She always knew what she was doing with an outfit, even if she was always saying how little she tried. She wore dangly earrings. She never left the house without earrings. She wore hoops sometimes, even though I’d always thought of hoops as adolescent, my ear piercings had closed over years before.

This night she wore chandeliers, black and silver, cheap, but over the top enough not to matter—with her cheekbones, her skin, they worked. The busboy would not stop staring at her. He kept coming over to refill our waters. Even when I stopped drinking mine altogether to get him to stop, he would find reasons to stop by our table, changing out our silver, refolding her napkin when it fell off her lap. He was bore-ishly attractive, young, broad-shouldered, dark hair, shockingly blue eyes. She pretended not to notice him at first, to be enmeshed fully in our conversation. But we spent every day together, every night and morning. We talked about the same things again and again.

She let him look at her. I saw her feel him, saw her turn her body toward him without letting him catch her eye. When he finally spoke his accent was thick, South Boston, born and bred. He didn’t ask her anything when he spoke to us. He said something about the food as he dropped it at our table. I buried my face into my plate in order not to stare him down as he continued to look.

He left her a note, scratchy handwriting, a pen borrowed, no doubt, from a waiter, he’d written his number and the word “drink” with a question mark. I was still hoping we could just laugh about this later. I was still thinking if I ignored him she would too.

It’ll be fun, she said. We’ll go together. I didn’t want to. I wanted to scream and cry and wrap both of us inside the tablecloth until we were home and no one could touch us with their eyes or food or drinks or pens or hands. I want to go, I said. Fine, she said. Her voice meant I would go. She’d stay.

For weeks, she disappeared for days to be with him. She’d given up her lease and was staying with me, so I always knew where she was at night if she wasn’t across from me in bed. She said she didn’t know the last time he might have changed his sheets, made fun of him in front of me. She was affecting this not caring, I thought. She was proving to me I still mattered most of all. The sheets, she said, had hard white stains from either their own coupling or his with others, maybe all the thousand times he’d jerked off in his bed before they met. I hadn’t changed my sheets either since we’d met. He had dropped out of high school, lived with a cousin in South Boston, had no real plans past the next day or week. She said when he fucked her he got angry just before he came and she liked the way his ass felt, taut and small compared to the rest of him, held in her hands. Twice, she showed me bruises he’d left across her body. I ran my hands slowly over them, one on the shoulder, another just below her chin, her skin so white and poreless, even in summer, the purple splotches popping, angry, with smaller patches of brown and blue.

Later, I reached my hand slowly up into myself with that same hand and let myself remember the lump of them, her pulse thrumming, I thought about their fucking, imagined the feel of that taut angry ass over top of me.

When she talked about him, it was his violent strangeness, which I understood was why she’d chosen him over all the others who approached her, over the PhD’s, the bankers, apologetic, anxious grad school kids. I liked the sound of him, even as I hated every second she was not with me. I liked all the ways I felt like I was another, more sustainable, version of him. I thought I might be another, maybe more destructive, violent strangeness to which she wanted to hold tight.

He stopped returning her calls after a month of this. She pretended, at first, she didn’t care. Then there was a week she told me she thought she might be pregnant. She refused to take a test, but left a message on his phone to tell him she was late.

I went to the CVS and bought the test for her, but she refused to take it. Instead, she curled up next to me in bed and cried. When he still hadn’t called her back a week later and she was still calling, warning, saying she’d take care of it herself except she didn’t have the money now, I found a used tampon in the bathroom under two sheets of paper from the day’s news. My roommates had both left for the rest of summer. We were the only two women in the house.

I left it there, exposed. My hair grew back.

Lynn Steger Strong‘s first novel Hold Still comes out in paperback March 21. She teaches at Columbia and lives in Brooklyn with her family.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.