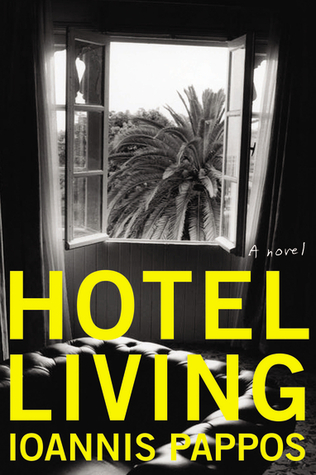

Nothing succeeds like excess in fiction — excess, and the inevitable downfall it foreshadows. You realize that all the sexual escapades and expensive art that Joris-Karl Huysmans’s dandy protagonist in À rebours racks up won’t fill the massive void in his soul, that the sprawling and ornate Gilded Age homes around Fifth Avenue in Edith Wharton’s novels hide dark secrets within their walls, and the gin at Gatsby’s house parties will have to stop flowing sooner rather than later. The good times, the really crazy and hollow thrills, can’t go on forever, exemplified by a small canon of books that hammers this message home. You, the reader, are an accomplice in each and every Dionysian downfall. With the cocaine-soaked Hotel Living, Ioannis Pappos has given us the latest of these great novels. It’s enough to make you feel terrible if it wasn’t so damn stylish.

Hotel Living focuses on Stathis, a Greek man with a great mind who takes full advantage of his ticket out of a nowhere village and navigates through the post-dot-com and 9/11 financial landscape. Stathis works as a management consultant for a company whose higher ups use a lot of new millennium workplace terms, and you get the feeling they don’t really produce anything anyway. They’re in the business of being a business, in that very 21st century sort of way, like how Paris Hilton became a celebrity simply by being famous. Stathis, like the book’s title implies, goes from one temporary living situation to the next, drinking more, smoking more, eventually falling in love with a journalist from a well-to-do East Coast family, and then watching that relationship come to a very bitter end. And that is just where the downward spiral begins. He descends into a Dante-like nightmare of drugs, booze, and sex with different men. While we’re led to believe the drugs and alcohol are to blame for his downfall, our compassion as readers all but runs out.

But yet, you can’t for the life of you put the book down, no matter how badly you want to hate Stathis, and it’s because of the same thing that keeps readers glued to books like Money by Martin Amis, and the Patrick Melrose novels by Edward St. Aubyn. This is the type of novel that is filled with a lot of terrible people and the terrible things they do and say, something the protagonist becomes more oblivious to with every page you turn and every line blown.

“I ran into decadence,” Stathis says at one point, as his life spirals out of control. He says this, of course, while he watches two people engage in a sex act involving an Oscar trophy. “I hear compassion through cocaine” he says after finding a place to stay. Even his interpersonal relationships are toxic to their very core.

Stathis’ job is the ultimate locus of his displacement. His work propels him from place to place, from posh Los Angeles hotels to a “don’t-wake-me-up suburb” right outside of Chicago, where all he can do is smoke and jog (“You are a consultant. You live where you work,” a friend says to him at one point). Like predatory teacher in Alissa Nutting’s Tampa or the director John Self in Amis’s Money, the job is an enabler; it puts Stathis in a position to do bad things. He might not be a bad or disturbed person, but loneliness and alienation combined with drugs trigger something dark and ultimately horrible in him, much like John Self.

At the end of the book, we see a little light in the darkness, a bit of a glimmer that gives us hope that Stathis can pull himself from the depths, but then we have to wonder if we’re OK with that. Is he even worthy of redemption? You could blame any of his misdeeds or transgressions on the indulgences of a new country, where an immigrant genius never quite escapes his outsider status, but then you also have to remember that he really has nobody to blame but himself. The dirty feeling the books leaves you with is repulsive, but appealing: it’s like you witness the rise and very messy fall of a party that started out great, but got dark near the end. Either things will get cleaned up, or they won’t; but that’s the great thing about a book like Hotel Living: that isn’t your problem. You can just enjoy the ride.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.