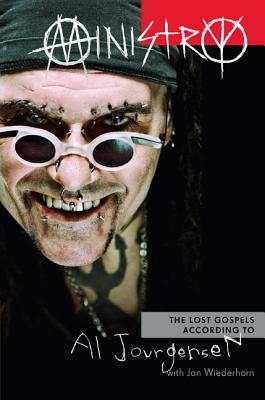

Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen

by Al Jourgensen with Jon Wiederhorn

Da Capo; 278 p.

In the collection of moments of stylistic dissonance that is Stephen Spielberg’s 2001 film A.I., one choice stands out in particular. Partway through the film, the central characters end up trapped in a rural fair, the sort of place at which families attend as one, musicians play on homey stages, and unhealthy food is consumed en masse. (Admittedly, this county fair is also one in which robots are destroyed in front of cheering crowds, but still.) At one point, during the night’s entertainment, a band can be seen playing to a crowd of families. This band is none other than Ministry, the long-running industrial duo whose songs exhorted world leaders to fuck off, whose videos told you everything you needed to know about heroin addiction, and for whom skulls and demons were commonly used imagery. The transgressors of one century become the family-friendly entertainment of the next, the film seemed to be saying.

Maybe I’m reading too much into that. In Al Jourgensen’s memoir Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen, the band’s founder and frontman details their involvement with A.I. This began with the project’s inception at the hands of Stanley Kubrick and involved run-ins with both Stan Winston and John Williams — both of whom, according to Jourgensen, had a penchant for talking about themselves in the third person. (He bonded with Williams; less so with Winston.) And Jourgensen channels his frustration at being on a set alongside an animatronic bear — which, truth be told, is a fairly understandable reaction.

Industrial music’s profile and influence is on the rise in 2013. Though Jourgensen convincingly makes the case that his musical influences range from ZZ Top to 13th Floor Elevators to dub (he describes his work with producer Adrian Sherwood as a kind of education for his later work as a producer), the book also collects testimonials by musicians attesting to the breadth of his influence in this genre. Among those citing him as an influential figure is Trent Reznor, whose Nine Inch Nails are preparing to embark on a high-profile tour. That isn’t the only case of industrial music earning attention this year: Kanye West’s Yeezus yielded a number of think-pieces noting its sonic similarities to a genre associated with musicians like Jourgensen and Reznor and labels like Wax Trax; and certain high-profile postpunk groups (Vår comes to mind) also seem eager to blur the lines between genres.

The Lost Gospels serves as both an education and as a cautionary tale. Jourgensen is up-front about his two decades of addiction to heroin and cocaine, and the horrific effect that that has had on his life. One particular low point involves a colostomy bag; other tales involve a blend of braggadocio and rueful memoir, as with this reminiscence of damage done while on tour:

I read the Stephen Davis Led Zeppelin biography, Hammer of the Gods — that’s all pussy shit. They threw TVs out the window. We threw entire floors’ worth of shit off the roof, and it was on fire.

The Lost Gospels is up-front about the toll of addiction on Jourgensen’s physical and mental health, finances, and personal life. Interspersed with Jourgensen’s account are interviews, conducted by Wiederhorn, of other figures in his life. These range from collaborators (including Jello Biafra and the late Mike Scaccia) to Jourgensen’s wife and manager Angelina Lukacin-Jourgensen. At times, these counterpoint the rest of the book; occasionally, they’ll shed more light on a particular point, or offer a different (or even contradictory) point of view. The arc of the book is bittersweet: Jourgensen is able to kick his addictions and overcome a bleak depression, but the later pages adopt an elegiac tone, noting the passing of several longtime members of Ministry and related projects.

The range of artists mentioned in The Lost Gospels is expansive; we learn that, in some parallel universe, Aimee Mann might have been in an early version of Ministry; Jourgensen waxes poetic about his love of the Chicago Blackhawks; and Ian MacKaye and Jello Biafra turn up for their collaborations with Jourgensen. Jourgensen’s account of his friendship with Timothy Leary makes for some of the book’s most moving passages; William Burroughs also turns up, first through his books and later in person. Jourgensen notes, regarding Naked Lunch, that “if you want incentive to either start or stop doing heroin, you can find it in that book.”

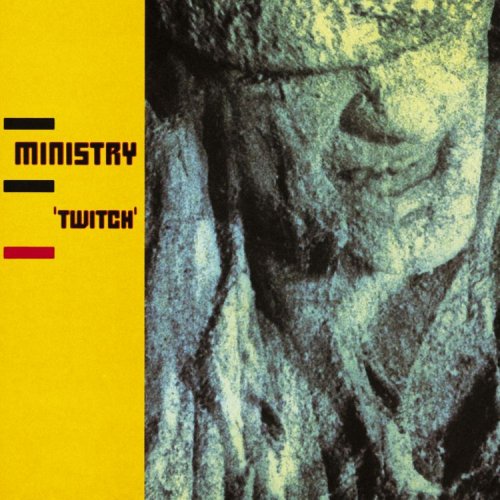

Between the extensive discography of Jourgensen’s works in the back of the book and the books and records mentioned, The Lost Gospels serves as a good primer to a particular corner of outsider art and music. And sometimes, its its uncompromising way, it’s tonally reminiscent of James Ellroy’s My Dark Places — the story of someone with a penchant for provocation and talent to spare. It’s also a reminder that Jourgensen’s made some vital, gripping music over the years — and it helps reveal some of the techniques (some of which were very unexpected) used to create that music. Whether it prompts a reader to revisit Jourgensen’s music, or to delve into his influences, time with this book is well-spent.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.