Sometime in the past year, I started thinking of myself as a year older than I actually am. Whereas before — say, at the age of 35 — I’d end up hesitating, considering 34, and then realizing that, no, I needed to go up a year, I now keep wanting to refer to myself as 37, whereas I’ve still got a few months to go until that birthday comes around. It’s a minor thing, sure, but it’s getting under my skin a little. Between this and repeated viewings of The Lonely Island’s “Diaper Money,” I am indeed feeling like the proverbial grown-ass man.

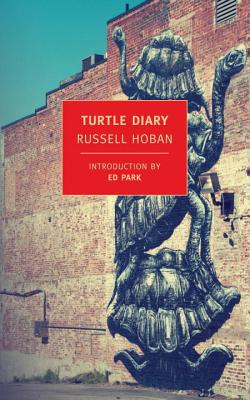

So, yeah, I’m that guy who’s going to connect “Diaper Money” to Russell Hoban’s elegantly constructed, carefully observed Turtle Diary. But, yeah, I kind of am — if only to say that the two are both, in their own way, about the question of adulthood’s compromises — and whether, in fact, certain avenues of potential are closed off after a certain point. The two narrators of Hoban’s book — a successful author of children’s books and a divorced man working in a bookstore and prone to unpleasant outbursts — both begin to fixate on a group of turtles living in the London Zoo. A plan is hatched — but, though there is an element of a caper here, the plot of Hoban’s novel veers into unexpected directions: some incredibly moving, some shocking, some quite tender. I enjoyed it considerably; Ed Park’s insightful forward also makes a connection between it and Renata Adler’s Speedboat, and the two would indeed make for a fine double bill somewhere.

My first glimpse of Turtle Diary came twenty years ago, as I can definitely remember my parents watching — and thoroughly enjoying — its 1986 film adaptation. And, hey, talking about generational shifts leads nicely into Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings, which follows a group of friends over the course of several decades, bright-eyed ingenues slowly becoming middle-aged — some as parents, some as leaders in their fields, others finding themselves more on the fringes. Wolitzer has plenty to say here: about shifts in art and technology, about class and its affect on friendships, about the effects of a traumatic event on the group’s dynamic. And, by and large, she does it well, working on a canvas large enough to make the shifts feel organic, and convincingly describing certain characters’ artistic successes. It works as well on the grand scale on which Wolitzer’s structure is set and in evoking the quotidian details of these characters’ lives.

In Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane, we also see one character in their early years as well as decades later. In this case, it’s the unnamed narrator — who, upon returning to his hometown for a funeral, visits a house near his childhood home and suddenly recalls a series of events he witnessed at the age of seven. These range from the traumatic but natural — the suicide of a South African boarder — to the much more uncanny. Gaiman’s novel is deceptively simple: though there is a strange cosmology present in abundance (including one concept that will be familiar to Sandman readers), this book’s stranger elements could also be read as allegory — a child slowly coming to realize that the world is more complicated (and more dangerous) than he ever realized.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

1 comment

No avenues of potential are closed off until you’re dead. I’ve proudly made NO compromises with “adulthood,” and I wouldn’t have it any other way. The number means nothing. I celebrate my birthday the way I celebrate New Year’s Eve. It’s a reason for a party and a new start, but the number is arbitrary and meaningless.